Trans-industrial pressure in Formosa: Taipei Biennial 2018

Museum of Fine Arts Taipei, 17.11.2018 – 10.03.2019

The first piece that greets the visitor to the exhibits of the 11th Taipei Biennial on the ground floor of the Museum of Fine Arts is a 100-foot long black horizontal timeline: The history of the spacetime continuum, by Rachel Sussman. The bit about us is packed into just five feet. Black frames indicate in handwriting significant events along the way, from ‘history starts’, the ‘Mayan calendar’, ‘Stonehenge’ and ‘Egyptians hieroglyphs’, passing by the ‘bronze’ and ‘iron’ ages rapidly towards ‘Shakespeare’, the colonizing of the Americas, ‘penicillin’, ‘nuclear weapons’ and the ‘anthropocene’, the new recently declared geological epoch characterized by human’s impact on earth. You then get to walk back in time, in a less clustered promenade, walking past the development of agriculture, notable examples of cave painting and the first known weapons towards the first dinosaurs, the major extinction of the Ordorician – Silurian, you’re around 450 million years before present by now, photo-synthesis is further down at 3.5 billion years, while, surely worryingly, the inception of the universe is as dense as at the present time, with nuclear fusion, superhot fog, and electrons all swarming in quantum fluctuations, receding from the edge point of 400 Million years ABB to the minute detail of the big bang. The piece, which is complemented in the exhibition by a series of photographs by Sussman of trees, moss, shrubs all characterized by their mind baffling ancientness, ie. over 2000 years old, invites a sense of perspective. This seems appropriate for the theme and concerns of this 11th Taipei Biennial, entitled ‘Post-nature: museum as an ecosystem’, which engages with the ecological consciousness and challenges of our time. Social scientists have pointed out that one of the issues pertaining to the containment of environmental ravaging on earth rests in the long-term range required by its solutions, which political institutions not to mention private bodies are for the most incapable of delivering, engulfed as they are in the daily grind of modern life. Time is of the essence

At first sight, the ground floor of the museum appeared to bring together works by international artists whose commitment to representing environmental issues and acting upon them continues to play a potent role in advocating collective social and political transformation. Helen & Newton Harrison have a large series of prints exploring Scotland’s possible alternate pathways out of destructive growth, towards sustainable balance in the context of irreversible climate change; Gustafsson & Haapoja present a Museum of non-humanity, a gloomy installation composed of multiple films mixing visuals with text-based definitions (in English and Mandarin) in a sequence of scenes radiating from nouns such as ‘person’, ‘boundary’, ‘animal’, that aim to correlate the categorizing of human versus non-human as a catalyst for discrimination, repression, and annihilation; Ursula Biemann immerses viewers into the sounds of the ocean, as we follow a moon-like explorer arrange her sensors on the coasts of Northern Norway, listening to submarine life, an approach that takes a gush of urgency when the protagonist turns to the camera to point to the pernicious effects of climate change on the traditional Sami ecosystem; Futurefarmers exhibit informative captions related to the heroic or hazardous conservation of seeds, such as the finding of a chest in 1965 in Goatland containing an array of historic wheat seeds, now being used to redevelop traditional varieties in Sweden. In this vein, the first two rooms on the first floor are dedicated to two chapters of Allan Sekula’s Fish Story, photographs taken respectively in the harbour city of Gdansk in the immediate aftermath of the Polish revolution, and Glasgow and Newcastle-upon-Tyne in the early 1990s, both tackling the painful process of deindustrialisation within the appliance of economic liberal policies in these traditional industrial heartlands. The biennial then, addresses through a range of works crucial subjects of present environmental debates, including industrial development, climate change, the commons, interconnected ecosystems, traditional socio-natural heritage, a beyond nature-culture divide in practice, and so on, those issues that stem from a ‘post-nature’ condition. One question then, would be, what of ‘a museum as an ecosystem’? The global trotter might be at ease with these works that tour the global art scene, but what of Taipei and Taiwan where this biennial takes place? It belongs to the other pendant of the show, that emerges progressively among this international display.

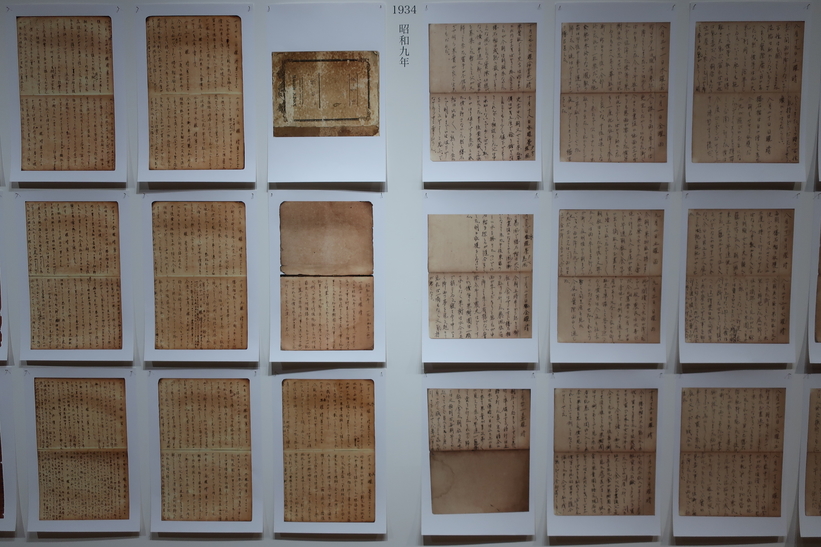

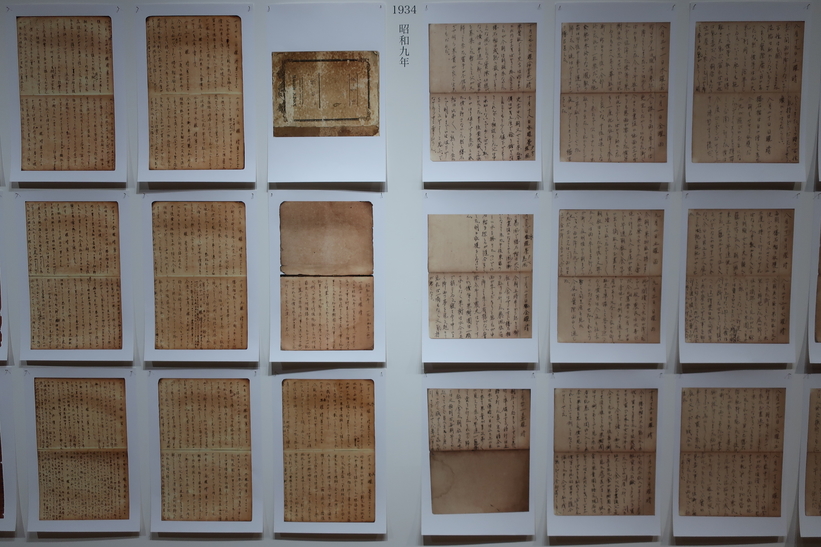

the diary of Lu Ji-ying

The 2018 Biennial, which ran until March of this year, was curated by Francesco Manacorda, of Radical Nature Fame (Barbican 2009), and the artist Wu Mali, whose concerns and collaborative art practice would have fuelled the site-specific part of the biennial. First one finds an encounter with artworks that approach some of the key issues underlined above within the Taiwanese context. Chang Ting-Tong looks at air pollution in Taipei. The samples he took at diverse location in the capital city being documented on film, while ink painting by himself as well as participants in workshops held during the biennial explore a détournement of traditional Qi principles based on the samples’ results. In Huang Hsin-Yao’s Baileng canal documentary, the camera films, one shot after another, the myriad of units that make the irrigation system built in the 1930s on the Xinshe plateau in the centre of the island. A strangely hypnotic portrait, the Baileng canal documentary subtly captures the historic intertwining of water, land and men inherited from the Japanese rule period. This connection with the land is also beautifully portrayed in the display of farmer Lu Ji-Ying diary. We are told that Lu Ji-Ying was born in Southern Kaohsiung, and educated in the early 20th century within the Japanese colonial system. From 1933 until his death in 2004, Lu kept a diary, first in Japanese, then in Mandarin after the retreat of the Japanese government and the take-over by fleeing mainland nationalists. The diary touches upon life in its diversity, crops and technological improvements, sales and family affair, community life and leisure, as seen by a man working on the land in a century of fast-changing pace and fortunes.

Second, drawing from these apertures, the exhibit gives room to associations and activists who are presently engaged in defending and advocating for ecological rights and sustainability in Taiwan. The island initially entered a phase of modernization as a Japanese colonial laboratory. Post-1945, industrialization and technological investment continued on Formosa, first in the context of the cold war, subsequently on a more isolated road leading to the 1990s Asian tigers dubbed group and the world-known Made-in-Taiwan brand. It is the unforeseen or rather disregarded consequences of this economic development as they unfold in the present that local activists represented here address. One recurring issue concerns the rights, and their spoliation, of the aboriginal tribes, the inhabitants of Austronesian extraction who have lived on the island for centuries, prior to the arrival of Dutch, Chinese, rebels and loyalists, Japanese settlers, and the retreating mainland nationalist army. A film and outdoor installation by the indigenous Justice Classroom echoes the 2017 Ketagalan Boulevard protest against new regulations for defining Taiwan’s indigenous traditional territories. The modern and the century-long ways of life clash on the coasts, where military cement blocks disrupt fishing and plain appreciation of maritime nature, the land, where factory pollution drips into farmland, the mountains, where soil exploitation threatens local ecosystems. Along the main corridor on the first floor, wooden boards informed visitors on the activities of association such as the Taiwan Thousand Miles Trail, a grassroots movement that contributes to the formation of a network of nature trails throughout Taiwan, and the Keelung River Watch Union, a collective of several clubs working on the conservation and rehabilitation of this Damsui river tributary.

The heart of the biennial, in that respect, was to be found in one room on that upper floor, where the environmental documentaries of Ke Chin-Yuan were projected on multiple screens. Filmmaker and producer, Ke launched the program Our island in 1998 on Taiwanese territorial television. Twenty years after its inception, the program offers a remarkable panorama of Taiwanese environmental conflicts, aspirations and ongoing challenges. The films covered landslide risks and dam damage in mountain areas, water pollution due to pesticides, deforestation on land and underwater seen in the damage on coral reefs together with associated traditional livelihoods, wildlife extinction, as well as problems in conservation ranging from the difficulty of reintroducing the Taiwanese macaque, to unthoughtful reforestation. The main piece in that multi-layered room, however, was the most recent film by Ke entitled Our island: 30 years of environmental change in Taiwan (2018). Breath catching, the footage recalls the fights of environmentalists in Taiwan over the past thirty years, from protests again a titanium dioxide plant, a tragic gas explosion in Kaohsiung in 2014, to the fight against the Sixth Naphtha Cracking plant of the Formosa Plastics company, whose poisonous activities are followed to its equally nefarious decentralisation in Thailand. In one of the closing sequences, one of the long-dedicated environmental activists whose fights over the years the documentary has been recalling, sums up the situation: progress in advancing causes has been limited, but what has significantly changed is an understanding of the framework within which these are being disputed. No longer can one focus on effecting change solely at the local level. Sending away one polluter just displaces the source of the problem, it doesn’t solve it. Phrasing an awareness that environmental issues and their solutions are increasingly being played out on a complex planetary scale, the comment invites reflection and action that mobilizes networks of coordination at the global level. This, as in many resistance endeavours to macro-scalar phenomena, is a recurring challenge to implement grass-root visions based on the pace of local and regional communities’ demands and decisions. As an attempt to further this discussion within the institutional remit of the Taipei Museum of Fine Arts, the biennial organized a four-month long program of talks, engaging with topics such as ‘ecologic vulnerability and democratic resistance’, ‘social ecology’, ‘activism and artistic practice’, as well as workshops by local and regional Taiwanese civic and environmental organizations. On the last week end of the biennial, there was a good crowd of youngish visitors. When I visited during the week, groups of school children were being sensitized to the works and issues on display. Long term commitment appears to be key in effecting any significant alterations to the mindless path that is pressurizing environmental planetary ecosystems. The 11th Taipei biennial pointed to the potential and possible responsibility of artistic institutions in articulating and fostering a collective trans-generational environmental awareness. In mixing a range of contemporary artworks articulating present changing representations of nature, with the actions of eco-activists engaging with trans-industrial development and their repercussions in Taiwan, the biennial contributes to the ongoing political urgency of breeding individual and communal commitment to socio-ecological resistance.

Gabriel Gee