In conversation with John Low

at the Centre for Contemporary Art, Singapore, March 22 2019

The Singaporean artist John Low talks to Gabriel Gee about his artistic practice and research on the legacies of Chinese Ink Painting in Singapore and South East Asia, characterised by a deep interlacing of aesthetics with historical heritage and socio-political forces, shaped by the maritime migrations of the turbulent 20th century.

Interview transcript with the assistance of Daniela Baiardi.

John Low's studio during his residency at the Centre for Contemporary Art, Singapore @John Low, 2019 Residencies OPEN 25-26 January 2019 Courtesy NTU CCA Singapore

Gabriel Gee: The numerous Chinese legacies in Singapore are particularly interesting. My focus is currently on trying to find the commonalities between Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan, all maritime cities-islands, and their imaginaries. I have been interested in the generations of artists who migrated from China, some who came and then left, so whom stayed. Can you tell me a little bit about your current research and residency at the Centre for Contemporary Art and how it came about?

John Low: What shall I say? My initial proposal to CCA-NTU, was to research on the notion of contemporary Chinese ink painting in relation to contexts of place and identity.

This idea evolved out of my research work on formation of subjectivity among Chinese artists here in Singapore’s modern art history. I wasn’t schooled in Chinese but in a missionary school, in the English language. I realized that I need to learn Mandarin well in order to engage meaningfully with translations. It is also a personal project as the saying “Turng nang buay heow tar turng nang whay” (i.e., A Chinese man who cannot speak Chinese) is something I encounter often.

For me, there are two main questions that come from those who articulate a critical stance: the first question, is what is Chinese ink painting, and what does it mean today? The other is where is Chinese ink painting today? To answer these two questions could stretch a pretty long way.

What is Chinese ink painting? It is defined either through its medium and materials, or through a cultural context, or both. As a matter concerning its identity, communally or individually, i.e., one sees the ‘man in the work’, as written by James Cahill, how has it evolved here in post-independent Singapore? There are also debates on whether the word “ink” should be deleted from the label.

Has it developed from a singularly particular or a diverse, pluralistic tradition and cultural heritage that have been transmitted here, one which is peculiar to Singapore Chinese society? Is it involved with a larger Chinese cultural tradition or one that is involved with a nationalistic, multi-ethnic cultural concerns? Is there a central operating concept, like for example, the concept of “cultural China”?

Singapore is a pluralistic society. It also experienced a period of colonization under British administration, from 1819 to 1963. In the political, social and economic contexts stemming from British administration to post-independence, how have meanings and notions of subjectivities, sense of place, been constructed in relation to these nationalistic/communal interests? How is this cultural heritage positioned, with regards to its development, or on the contrary its stagnation? What are those values that the Chinese here identify as part of their heritage, and have these evolved?

There where is Chinese ink painting today, seems to point to its absence, or its direction when the practice becomes diverse, in the Singaporean contemporary art scene and thereby having an implication on the question of its identity. Could the medium and its identity (Chineseness) be separated and how, by what means?

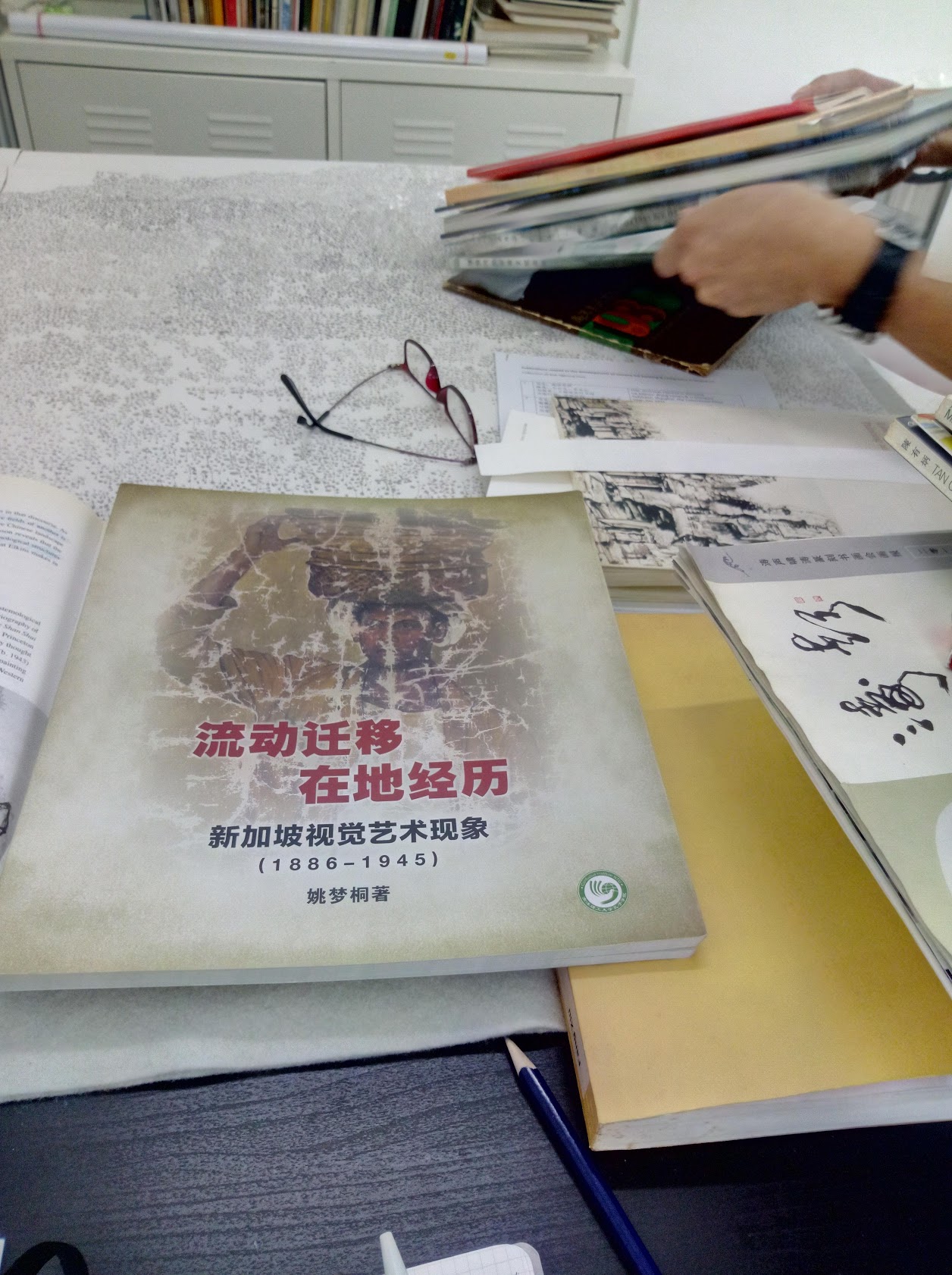

My research proposal engages with two aspects: One is visual research, everything that you see here in this room. The other is contextual research. This is assisted by a friend of mine, Koh Nguang How. All the books we have here in this room are from his archival collection. He is an archivist, and he has been collecting documentary materials on artistic development here in Singapore.

@John Low, 2019, Residencies Open 25-26 January 1019 Courtesy NTU CCA Singapore

G: He did a residency here at the CCA as well.

JL: Yes, he did. He is not only interested in art works, but also in the development of the Chinese community here. In a sense we need to dig out more in order to place modernist development of Chinese ink painting in Singapore. To me what’s missing in this archival collection that is on display here, is mainly its relation to the development of Chinese literature, known as Malayan Chinese literature. The compilation of works of Chinese literature in Malaysia, or the then Malaya, was initiated by Fang Xiu. Of his many works, only one has been translated into English, i.e., Notes on the History of Malayan Chinese New Literature, 1920-1942, tr. Angus W McDonald, Jr., The Centre for East Asian Studies, Tokyo, East Asian Cultural Studies Series, no. 18, 1977.

Fang Xiu was a former journalist, writer, and teacher. He went around library collections, to painstakingly copy down all the various literary writings in Chinese. These are published in a ten-volume work, that to this day has not been translated. It can be said that he has an interest in proletarian literature, which followed then, the development of proletarian literature in China during the Republican era. In that ten-volume work, you have collections of short stories, art reviews, pieces on opera and music, and theatre, and so on. That ten-volume work portrays a particular cultural development of the Chinese literary circle in Singapore and the then Malaya. Other authors have also made their own compilations of literary Chinese writings, differing in content from those of Fang Xiu’s work. In its historical development, there was a shift. In the earlier part of its history, the Chinese writers mainly wrote for an audience in China. By the 1920s, there was a shift to localize literary writings, thereby identifying its concerns with a sense of place, that is Nanyang, its local flavour and colour. Nanyang refers to the regional geographical remit of Southeast Asia and is itself a problematical term.

G: Nanyang was a term that was formally presented.

JL: In a way yes. Yet when studying its history, it does not seem to fit very well to the situation. Back then, its usage in China meant the South Seas. Regionally, in Southeast Asia, it is made up of the many port cities, constituted by businesses trading networks, what they call Guanxi (關係). And these various port cities were connected with the southern coastal cities in China and Hong Kong. After World War II, when nation states in Southeast Asia, sought their own independence, Nanyang as a regional term became problematical. The formation of ASEAN in 1967 may facilitate a re-connection, but that is governmentally problematic I could think.

G: It corresponds to the historical path of the Singapore and Malayan state. The Nanyang Academy was created before the war, in 1938, so these aspirations correspond to a certain social context which changed with the move towards independence.

JL: I don’t know if this aspect has been written, as up to now, I have yet to cover relevant materials written in Chinese; it’s a position that the Chinese thought about for themselves. Its establishment in 1938, sees a concern for cultural development in what was termed a cultural desert; literary development has already taken roots, the concerns for the development of visual culture was then just as crucial for the Chinese enterprising community here. Then, the Academy has its modernizing concerns as well, especially its development of a Nanyang School of painting, with emphasis on local flavour and colour. Other historians may prefer to use the term “Malayan School of painting”. Could its development/establishment, parallel a later concern, the establishment of Nanyang University (Nantah)? How would the Chinese community here see themselves pre- to post-WWII and independence, were there any differences? How would these two institutions work for the development of the Chinese community here? But Nanyang University has merged with the then University of Singapore to form the National University of Singapore in 1980. It has been renamed Nanyang Technological University. Lately in the 1990s, concerned scholars were asking for its former name to be reinstated. Social and cultural developments were tied to nationalistic concerns. Was there a pull towards a diversity away from these nationalistic concerns? NAFA’s diplomas were only recognized from the mid-1990s, when it received educational funding from the government. From a privately-funded institute, to one that is publicly funded, one wonders what will be its future outlook. It was projected then, that both NAFA and Lasalle will conduct their own degree programmes under the National University of Singapore, but that didn’t happen.

G: In parallel, there emerged in the 1960s the influence of the modern artists association. They were also very influenced by the western education, through Japan, China and Europe, particularly in France through Georgette Chen. Yesterday you were telling me that you have to be actually be careful with this western and eastern division that you had in Shanghai and that was imported, in the sense that it was not an absolutely separated realm, and they managed to have some form of dialogue. With these modern practices, you had people who wanted to develop more formal practices, and others who wanted to engage with this new regionalism, or trans regionalism.

JL: The east/west division, as seen in artistic development here, I think, has yet to be fully research. For me, I focus on how the intellectual debates which were carried out during the period of Republican China were transmitted here and how localization developed or whether it was truly transnational, has yet to be seen. There were many debates carried out in Republican China. Besides debates on the practice of modern art with differing interpretations from Japan and Europe, there were other issues such as, elitism/classicism versus nativism, a racial discourse (the yellow peril) which includes eugenics and sexuality, what is native-soil literature, etc. By the 1960s, or up to the 1980s, were arguments such as the East is spiritual and the West, material, still floating around, and has this influenced the development of attitudes towards modernist art here. Another example could be Cai Yuanpei, (Tsai Yuan-pei), the Minister for Education during China’s Republican period, who argued for replacing religion with aesthetics. His educational policies could have an influence on the Chinese educators who migrated here. The writings on art by Lim Hak Tai, the founder of NAFA, do reflect the thoughts of Cai Yuanpei. Though Cai Yuanpei’s thoughts were influenced by European philosophers, there are some arguments that it is Confucian in outlook.

The mainland Chinese had produced book such as this: Methods in aesthetic training. A New curriculum in elementary Schools, this was published in Shanghai in 1925; How to teach the industrial arts; 1925; The fundamentals of painting, this is 1932, Fundamentals of Colours. All these books were the ones Koh Nguan How salvaged from Chinese school when they closed. In one of these books, we found the idea of learning from both east and west being promoted. We didn’t realize that this was circulated amongst various Chinese schools, whether those Chinese teachers in elementary and secondary schools were really developing a curriculum along that line, we have yet to see. Were these books (instructional manuals) made available to students? For me, I wonder, in practice, whether the ti-yong dichotomy was still at play, i.e., Chinese tradition as substance (ti), and knowledges of the West as “function” (yong). For me, studying at NAFA in the early 1990s, language was certainly a problem.

Besides Cai Yuanpei who was here earlier, on transit to Europe, and later, two other well-known mainland Chinese artists, Xu Beihong and Liu Haisu came in the late 1930s. Have their ideas and approaches, as in the development of guohua in China, influenced the modernist approach towards art-making here and how were thoughts on localization formulated. Were the debates concerning Xu Beihong and Liu Haisu back in Republican China, transmitted here? Liu Haisu did not have an easy time, as he wasn’t trained in Japan or Europe, though he visited these countries much later in the 1930s.

Certainly, after 1949, there could have been a break, which may have initiated a concern with regionalism, especially, in an attempt at fully realizing the richness of what the term “Nanyang” meant. In our context, especially “The Ten Men Group”, has this regionalism, being informed by the study of jinshijia (Studies of bronzes and stones) or the kaozhengxue (School of Empirical Research, which literary means “search for evidence”) movement of the early Qing, which have an influence on the Shanghai School of Painting, and how this contrast or coalesce with the study of Primitivism in western modern art, I have yet to prospect. Or, has this been locally inspired by the pioneer generation artists who went to Bali in 1952? There is also a history of travel literature in China, where artists/writers paint/write for the arm-chair traveller. And the May Fourth Movement is still being remembered here and this puts forth a dilemma, is there an intention to re-connect after all the turmoil China had experienced? To re-connect to/with what?

The exhibitional catalogue of Yeh Chi Wei (of Ten-Men Group), show his collection of traditional Chinese ink painting and calligraphy, reproductions of ink rubbings of various types of ancient scripts (oracle bone script, stone drum, etc.) and other indigenous artefacts from Southeast Asia. His “Western” modernist-style artworks sit among this collection. This is similar in nature to that of the literati painter’s studio in dynastic/Republican China. The literati painter paints in the xieyi mode, and his studio is filled with beautiful handicraft artefacts from well-known professional craftsmen. When I look at the ancient script rubbings, I am reminded of how ancient these are. I believe the Chinese is not going to let their civilization disappear.

Another approach could be that they were defining modernism/modernity through Chinese ink painting history/theory. Though arguments were posed lately that suggest modernizing elements occurred early in Chinese ink painting history than in European art history, one wonders whether artists like the Ten-Men Group were making their initiatives in like manner. If I am not mistaken, there was a proposal to do a comparative study between Song China and the Italian Renaissance, but it was subsequently changed to Art in the Age of Exploration: Circa 1492. The initial proposal didn’t seem scholarly in approach.

Both the formalist, regionalist, and trans-regionalist were certainly approached through subjective attitudes and whether these were constrained by formalistic definition of aesthetics could be seen through a selective adoption of western modernist artistic styles. That the Nanyang style has the possibility of exhibiting “multiple/alternative modernities” has yet to be seen.

I do see this development in societies such as the Equator Art Society. They were social realists, seen as portraying social injustice. I do not know if when using this term, we are a pushing towards a socialist way of thinking, or otherwise, an engagement with that period of time.

G: My impression was that the Equator Art Society represented a distanciation, from precisely, traditional aesthetics coming from China that didn’t engage with contemporary issues.

JL: Distanciation from Chinese traditional aesthetics? It might seem so, depending on discursive “framing”. There was certainly a process of sinification at play after Mao Zedong won leadership of the Chinese Communist Party. The purging of the communists by the Republican Nationalist Party certainly made politically engaged artists moved towards developing a leftist cultural programme. The Cultural Revolution eradicated much of the earlier practices in various modernist styles, and it was after the death of Mao that other forms of thoughts came into play.

The Equator Art Society was active from the mid/late 1950s to the early 1970s. There was a lapse in re-registration. Societies here need to be registered formally. But many things happened here in the early 1970s. There were the racial riots of May 13th 1969 in Malaysia, to the National Cultural Congress in Kuala Lumpur in August 1971, and to the non-admittance of Nantah graduates to the University of Malaysia. Over here, there was student political activism, a few editorial staff of the Nanyang Siang Pau, a major Chinese-language newspaper, were arrested, Nanyang University was made to change its teaching language to English. In 1971, protesters demonstrated against the prolonged detention-without-trial of the 1963 Operation Coldstore detainees. This was the period of the Cold War.

The 1970s also acknowledged the emergence of the then “contemporary” in artistic practices here and in Southeast Asia, one that is international and conceptualist in its approaches. This may be contrasted with the Modern Art Society, who were mainly into abstraction.

This association with different historical pasts and contexts, questions the manner in which it is framed to engaged with our local contexts. In the 1950s, especially the later part of the British administration’s political tutelage devolvement towards independence, led these artists to questions pertinent issues of the times. By the 1970s, the multinational corporations were here, with foreign talents to develop the industry. Progress and development could be seen differently, and perhaps there was a rethinking of their aesthetical approach. Perhaps by the 1970s, questions concerning national identity and the identity of one’s artistic practice, were personally being re-thought in a different way.

Perhaps, the issue of Confucian ethics might possibly bridge the gap, as socialism and Confucianism are seen as incompatible systems of statecraft. Will this narrow the issues of distantiation?

During the Ming dynasty, there was a branch of Confucianist thought known as the Taizhou School, founded by Wang Gen (Wang Ken, 1483?-1540), a commoner and a salt merchant. It was during a time, the later part of the Ming dynasty, when merchants trade and take pleasure in the Confucian Classics, putting themselves as equals with the scholars. This school simplified Confucian doctrines and disseminated them among the populace, through guilds and lineage associations. Someone has described them as sages in the streets. In Confucianist statecraft, they stand on the left, hence they are easily appropriated by today’s left. One of the most important concepts which they converted, is liangzhi (innate knowledge) into liangxin (conscience). The concept of conscience as a moral reference for daily life among the populace, could have floated among modern cities with trading network connections and in the schools. It’s a sphere of influence yet to be investigated. I am working with a potpourri of fragmented ideas.

G: What about the artists, who around this period, in the 1960s tried to mix calligraphic style in the Chinese tradition, with contemporary subject matter?

JL: I am not aware of such works of the 1960s, especially if it concerns contemporary subject matter, the closest could be paintings of ethnic/native subject matter, as we understood the term today. At present, my research concerns its historical stylistic/theoretical development in China, before I turn to the local context. For example, there is such a practice called “Three Accomplishments”, which combines painting, calligraphy and seal-carving into one, besides the “Three Perfections”, painting, calligraphy and poetry. Besides subject matter, were there innovations within, stylistically, or painterly.

The artists that comes close to this subject is Cheong Soo Pieng and Chen Wen Hsi during this period.

It would be rare to see contemporary subject matters of the 1960s in Chinese ink, but we do see them in different mediums, such as woodcuts. Most of us were not aware of these, till the late 1990s, as shown in History Through Prints: Woodblock Prints in Singapore, at the National Museum Art Gallery in August 1998.

G: You can see different traditions at play in these works.

JL: In a way yes, to me in terms of subject matter it seems rather limited. It seems to follow a tradition, reinterpreting it. I do not know if whether it’s innovations within the tradition. Ek Kay was of those who went overseas to study. He studied in Tasmania, and then Sydney. If you look at the works of these younger generations, you can see that the Western influences are much stronger. Compared to works showcased at the recent Explorations exhibition at NAFA, calligraphic work by elective students, you will find that, though there is a diverse approach, one seems to hold to tradition and commitment to innovation, yet, maintain and remain within that cultural heritage. It seems, there is a diversity, but yet, repetitive. It seems that graduates from NAFA, seem to think about change through a westernized approach. Whether they are aware and want to acknowledge that influence it is uncertain. It is not readily recognized when you read through the essays, especially, the role of knowledge from a western art history perspective coming into play in the development of the Ink Painting tradition.

Sources of influence are many, mainly from China, Taiwan and Hong Kong, as these are seen as major centres of ink painting. For me, it can be difficult to identify the different traditions at play. The major issues for me would be whether to read them in terms of “spirit”, and how do we interpret this term today, and in terms of “styles”.

G: Traditional Chinese practices in the literati tradition tended to be private, and engaged in an introspective quest. The work used to be shown to fellow practitioners, but was not meant for a large public. Has this been so in Singapore?

JL: I suspect that the early public exhibitions of artworks here did not occur until art societies and institutions were formed, where their large collective membership could lend support in terms of logistics and finance. They could have known of earlier exhibitions held in China, and seen their benefits. See Chen Shizeng’s (1876-1923) Viewing Paintings (1918). With regards to traditional Chinese ink practices, in particular the earlier generations, we are aware of stories about painters, local and invited ones from overseas, who painted in the presence of friends. There is an art eco-system, though it is not fully documented yet, where philanthropic merchants/collectors, sellers, artists, local and foreign, could make connections. These spheres of influences have yet to be fully studied. Prior to the establishment of museums, clans/guilds trading networks could play a large part in this eco-system, with connections between the port cities of Nanyang (South Seas), the southern coastal cities of China and Hong Kong. Private collections also serve as libraries, where interested parties gather to study and discuss the collections. The founding of NAFA in 1938 won’t have been realized without the existence of this art eco-system.

There was one event that shocked the community. Low Chuck Tiew’s (1911-1993) Xu Bai Zhai Collection was donated to the Hong Kong Museum of Art in 1992. When institutions are not helmed by knowledgeable expertise, the perception that Singapore was once a cultural desert persists. The collection’s historical importance of Ming and Qing dynasties paintings, could have been missed. The richness of a port city and its transnational networks, and how they contributed to artistic developments are not explored. Will the concept of “cultural China” remains fuzzy?

When news of this donation to Hong Kong was heard, two shows on Chinese ink were held. “The First Ink” Exhibitionwas held in 1991, the second, Journey of Ink in 1993. The second exhibition showcased a few Chinese ink societies: Molan Art Association, Siaw-Tao Chinese Seal-Carving, Calligraphy and Painting Society, and Hwa Hun Art Society, while the first focused on the earlier pioneer Chinese artists. But this is not to say that there were no other shows on Chinese ink. National Museum Art Gallery opened in 1976 and Singapore Art Museum in 1996 and Chinese ink art societies do hold their shows annually or periodically in other exhibitional spaces.

There are two incompatible systems of historical writing in Chinese ink painting histories. One is written by the Chinese themselves, and the other, by the English-speaking academia art world. It also involved with various aspects of modernities, either through an interaction/engagement with western modernism or innovation from within. I felt that many of these exhibitions were framed in the former, very much unlike the work of James Cahill, who believed that Chinese ink painting is to be read by all. One glaring concept that comes to mind, is that of the Dao (Tao) of painting. Whereas art historians like James Cahill would advocate caution in dealing with it, the Chinese runs with it, its metaphysical concepts come strongly to the fore.

When I was working on this residency, I asked myself whether the idea of exhibiting the work as a practice, in relation to this communal spirit engagement, is feasible. I do not exhibit with objects but I exhibit a practice; with a community of like-minded people coming to engage with it. The question of how do we exhibit this practice, remains.

To me the strength of Western art is palpable, naturally then practitioners influenced by this tradition would treat the studio as a private practice space where they, in solitude, could work. Another related concern is with intellectual property, and with the concept of “originality” which I could like to explore in traditional Chinese ink. The concept of the artist working in solitude alone in his studio, seems to be related to this, whether studies concerning these issues concerning this could be expanded. In China’s dynastic histories, once a painter’s work is popularly acknowledged, its readily forged. I once watched a video in which David Harvey commented that in China people take each other’s ideas, take them to another region, and used with modifications to suit. A merge between capitalism and socialist economy that is quite different from other countries.

This is an exhibition catalogue on …

G: from the National Gallery?

JL: No, a private publication done by the family. In studying this work, you will find an orientation towards innovation within the Chinese tradition itself. If you look at this artist, Lim Chu Suan, she did try to depict a peculiar approach to ink painting. She travelled with the Ten Men Group, they went around South-East Asia studying the landscapes and monuments.

G: Koh Nguang How did a project on the Ten Men group.

JL: Yes, in one of these projects, I followed him to Cambodia. We were tracing the routes these artists took, trying to find out what they were doing, putting ourselves in their footsteps.

G: Re-enactments can be very productive, going back to the site where celebrated artists once worked, as the French painter <…> did going back to find the exact spot where Van Gogh painted such church, Cézanne this coastal view, and incorporating the changes that have occurred on the territory. In this case there might be an opportunity to try to understand and get closer to an artistic drive, and possibly to invent a tradition.

JL: To me, I felt that the perception of aesthetics changed over time. I was educated in a very different manner, in Western Australia, whereas Koh was not schooled formally or academically, he gained his experience by working with the National Museum and artists. He is close to Tang Da Wu, and at the Artists’ Village in Lorong Gambas, where he started documenting its early history. Koh also mixes with the Chinese literary community as well, and through his archival collections is aware of much things.

So, at that time when we were in Cambodia, I was just a follower, listening to Koh’s observations and remarks. For me, the trip really opened up the various contexts in which the travels of the Ten Men Group took place. What is travelling, what does it do for me? For me, there was a time gap, a difference of maybe five decades or more. Were we seeing the same ruins? What we saw must have been ruins that were better preserved and more complete than what the Ten Men Group saw.

In exploring that trip I did not fully understand yet, the nature of their aesthetics or artistic styles, that the Ten Men Group were working on. What was it to be modern then? This question goes beyond the question of style, or is it tied to it? I could imagine that mapping Nanyang, as a region, travelling through its diverse culture and heritage is similar to travelling to the various ethnic regions of China. Similar, as in the sense of, what is the grand idea/narrative?

When one tries to depict the Nanyang style, a style that should be seen as multifarious, one senses that there must be a purpose, a reason why they were engaging with these territories, these landscapes and ancient monuments. Personally, I am not looking through a strictly art historical gaze, I’m looking from a socio-political-cultural point of view. It is the same with Malayan Chinese literature, writers don’t write for the pleasure of writing.

In Singapore, in our multicultural context with the various policies designed to handle those multicultural interactions, the Chinese had to be placed as a community equal to all the others. So, whether that becomes possibly a hindrance to the development of arts and culture, or its pull towards preservation of tradition and cultural heritage, seems to move in a tentatively cautious manner. As documented in Lee Kuan Yew’s memoirs, in the early days of our independence, the Chinese did ask him to make the Chinese language, the national language. The advocacy for a dominant Chinese position here in Singapore is very strong, I think it is still there today.

Today’s papers have an article on Hwa Chong, a Chinese-language school. The journalist mentions the school has been turned into a special assistance school; when the Chinese schools were closed in the late 1970s, a few of the best Chinese schools were allowed to teach in Chinese. Hwa Chong is one of them. There seems an intention to minimise for the purpose of grooming a cultural elite, where the best can engage with the difficulties of the Chinese language and its cultural heritage. But, again the message was to emphasize that the Chinese were only one part of Singapore culture. This kind of policies, on one hand one could say that they are hinderances to the promotion of Chinese culture, but on the other hand, in the diverse field that is Singaporean society, it becomes an incentive to push forth and continually develop that which makes it particularly distinct. I wonder if they come here and look at all these art catalogues, what would they think? Would they really see a difference with other places and affirm that the preservation is stronger here than in other areas? Is there a distinct Singaporean Chineseness?

On a different level, Chinese Peranakan culture has almost declined, most of its heritage has been museumified, its cuisine is the only item made palatable for tourists. The loss of its language (Peranakan patois – a mixture of Hokkien and Malay), and its cultural practice might be a reminder for most.

For me, the trip places in focus, through the time gap, whether there were different modes of thinking and engagement, spatially and temporally, in terms of what is Chineseness, now and then, or actually, there isn't that much of a difference, i.e., the modern as differentiated from contemporaneity.

Part 2

G: I was recently at the Kaohsiung Museum in Taiwan, where they have a prize for contemporary practices. It is organized by categories. You have sculpture and paintings, as well as a category for practices abiding to these ancient frames of reference, using calligraphy techniques, although often in very experimental fashion.

JL: Yes, I think it’s important to see new techniques, to do without the brush and works that destabilize categories. Ho Chai Hoo does work without a brush, and he creates his own ink. He is not bound to medium specificity. Here in the nineties, the argument was that Chinese ink paintings belong to a very specific medium, once you move away from it, it’s no longer Chinese painting. Material is deemed as part of its cultural heritage. I think a lot of contemporary practitioners and writers try to engage with this issue of categories, by moving away from such definitions. But for Chinese ink here, with a few exceptions, it’s still bound to its traditional subject matter and medium.

I think they push their focus on the notion of function. How does Chinese Ink painting function today? In the context of the art market it seems quite clear cut. But in terms of contemporary exhibition practices, how can we change its function. Many traditional subject matters in Chinese ink are tied to their symbolic meanings. How will the art market and art institutions work to promote contemporary Chinese ink painting?

For my residency work here at CCA, my research interest on contemporary Chinese ink is focused on what can the work do for me, or what can I do with it. I am not yet at the stage of meaning-making. Maybe, I don’t want to be there. It is research based, so how should it be exhibited?

G: There are many books involved as well…

JL: Yes, and how do we bring all these together. With regards to the archival collection here, we try to categorize them in various subjects, we have the different schools’ collections, such as the Chinese Ink Painting Society collections, from elementary to master/teacher levels, such as Fang Chang Tien who arrived from China in the 1950s, and taught many in Singapore. For instance, this is a recent show by Chua Ek Kay, a second-generation Singapore Chinese Ink painting artist who studied with Fang Chang Tien.

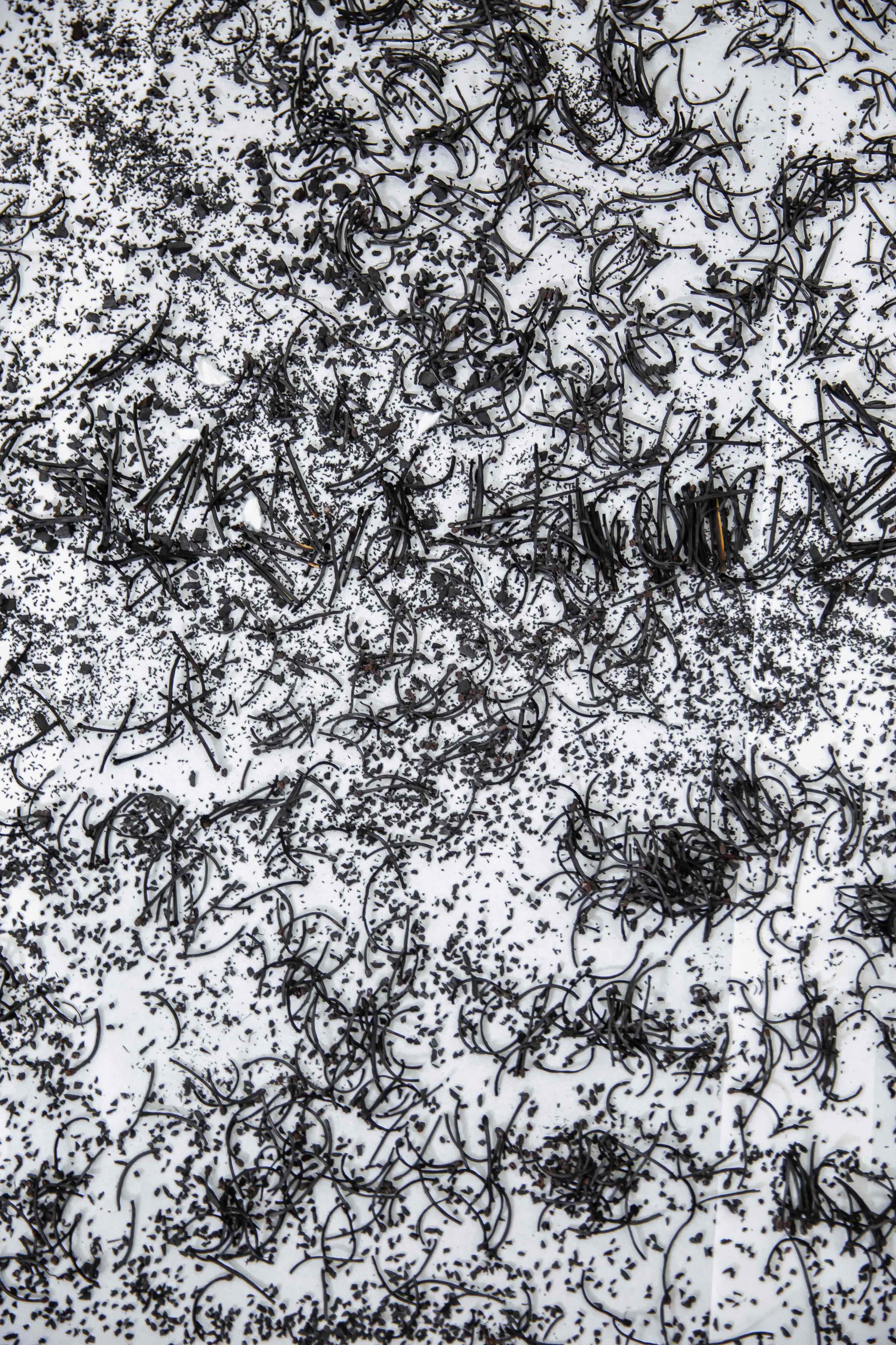

There are lots of trials and errors as part the research. Should these be displayed as part of a research process? But what you see here is similar to a white cube space. I did a floor piece, here, using charcoal, which I broke down into small chips of different sizes and burnt matchsticks. I had to get rid of it and because the fine charcoal dust was getting to the books.

I thought, can I use the word displacement? By displacing a wall piece to a floor piece; how does that change the work? It didn’t really work out, it’s problematical. This is an image from it, I allowed people to walk on it.

@John Low 2019 Residencies Open 25-26 January 2019 Courtesy NTU CCA Singapore

G: It makes me think of a young Chinese artist, Li Yani, who was doing a MA in fine arts at ZhdK in Zurich. She did a performance with a fellow student from Switzerland, in the main hall of the Zurich arts school, whereby they had a huge scroll on the floor, and dragging some ink in a bucket, and a huge brush, they would write characters while stretching the huge paper scroll through the massive hall. They alternated writing characters, expect that Yani was in fact making them up. They looked like traditional characters, but they were not. It was tradition reinvented.

JL: Pedagogically, we are at different ends. I first studied at NAFA in the early 1990s, and after a year I moved to Curtin University in Perth, Western Australia. At Curtin, we were taught to question art making. My tutors were involved in the art making of the 1960s onwards, so it was entirely a different world. At NAFA at that time, there is a strong disciplinary approach to techniques and realism, less emphasis on abstraction and experimentation. If you engage with the latter, there is minimal dialogue with the tutors. If one doesn’t develop a strong foundation, one can’t do good art. At Curtin, the dumpsters were where I looked for art materials and ideas. In my final year, my drawing class was a group performative class, we didn’t work with charcoal and paper, still-lifes and nudes, etc. The most difficult question posed to me was if I cannot be a successful artist, how can art make me a better human being.

There was also at that time, in Singapore, a phrase that was floating around, which is, “art is an universal language”. Art for art’s sake or art for society’s sake? – we had to sought out these confusions. Its later on, that I see an artwork as a personal historical document, and following a Foucauldian approach, how does man study ‘Man’ – the question of subjectivity? I’m interested in the relations between the individual and the community, and how these in turn are framed by larger social, political, economical and cultural forces. It was also usual for artists to use existentialist concepts to talk about their work. All these are rich materials for an ‘archaeology of painting’.

G: In the history of traditional Chinese painting, this tension between the rigid laws that commend an artist’s practice, and the innovation and creative imperative that can ultimately be attained by the skilled master, is very ancient. The history of Chinese art is long and distinguished, with periods more conservative than others, phases more progressive than others.

JL: Yes, one of Xie He’s (Hsieh Ho) six cannons of painting. I have read somewhere that ink painting manuals, such as the Mustard Seed Garden, played an important role to students of ink painting, even during the late Qing and Republican period in China. I have not yet come across a good study of this. The concept of “old age” plays a part in this artistic discourse. The NRM show I showed you earlier, we managed to talk to the tutor who was teaching this class. One of the questions I asked him, was: have you considered new ways to teach students, to find new modes of rethinking how Chinese painting can be expanded. I have come across friends who dropped out of their Chinese ink painting classes. One of the reasons was that they couldn’t associate real subject matters with those traditionally painted ones. These traditional subjects with their symbolic meanings, couldn’t be associated with their daily lives. It’s no more of aesthetic beauty alone, but what holds other significance in their daily lives.

It is quite hard now to find bamboo groves growing freely in Singapore, except in forested areas. When I was young, days prior to Chinese New Year, we harvested sprigs of young bamboo leaves, tied them into a bunch, and attached to the end of a long bamboo pole, we cleared the house of cobwebs that have built up under the attap roof. Cobwebs must be cleared by young bamboo leaves? I do not know whether that is pragmatic or symbolic then, but it was fun spring cleaning.

Our movement from kampongs to HDB flats, from large families to dispersed smaller family units, the closure of Chinese schools and with the loss of the older generations, customary practices and their knowledges were no longer transmitted to the younger generations. Were these associations of objects and their symbolic meanings lost over time? But I don’t see an issue with these. One can always google. But here, the concept of “memories” comes in, memories that are not constituted as part of history. I tend to read colophons on Chinese ink painting as memories. And the idea that painting is a disciplinary practice might irk many.

I think I would like to visit Dong Qichang (Tung Chi-chang, 1555-1636) writings. Though his division of Northern and Southern schools of painting has been disputed, and China has branded him as an anti-socialist, his argument on treating a landscape painting as a painting, one which has no reference to an actual landscape, seems promising. But in Republican China, the issue of realism came to the fore, as the means to modernize/nationalize traditional Chinese ink. In today’s practice, we have seen “the death of painting” – painting without history.

I wonder whether we could be looking at issues concerning epistemological breaks, histories of discontinuities and the importance of doing art history, whether academically or on one’s own, where innovations and progress were studied, marked, and charted. Maybe, this history was taught fragmentedly; contestations in how histories were written could also be a marker for disinterest. Histories ought to be taught in an inquiring manner, as it is a written discourse. Maybe that’s not how it’s done here. The loss of the Confucian Classics, especially in the manner of its doctrinal development and its practical implementations, may also be the cause for stalemates, stagnations, and innovations. And the concept of the artist-hero is something I do not want to deal with.

In China’s dynastic histories, tastes might be decided by the imperial courts. During the Republican era, Beijing and Shanghai were contested art centres. For us, the professionalization of the various fields of art, was only developed with the Renaissance City concept.

G.G: More generally in Singapore, you don’t really have foundation programmes in art history. The move is straight to master programmes.

JL: I do not know much now, as I have stopped teaching for many years. Back then, at diploma level, art history stops at Pop Art. We did not have time to cover Minimalism, Conceptualism and the postmodern and much lesser time to cover modern Asian/Southeast Asian art. I think now there is a change at Lasalle where the BA(Hons) is done over three years. But normally, art students cover art history in a fragmentary manner. Students do complain that the learning curve is very steep. Even though we do contextual studies, where we bring art history and art theory into studio practices, more time is still needed to bring about results. So there need to be continuity after graduation, and I believe there are many public programmes that lend support. But then, there is always an issue of what one wants to learn, what is of one’s interest, and these public programmes might not appeal to them.

There is the MA Asian Art Histories at Lasalle, which, if I am not mistaken has being running for more than a decade. But that is strictly for art historians.

G: Here you get people to visit the studio. Are you looking for another ways to staging or displaying the research?

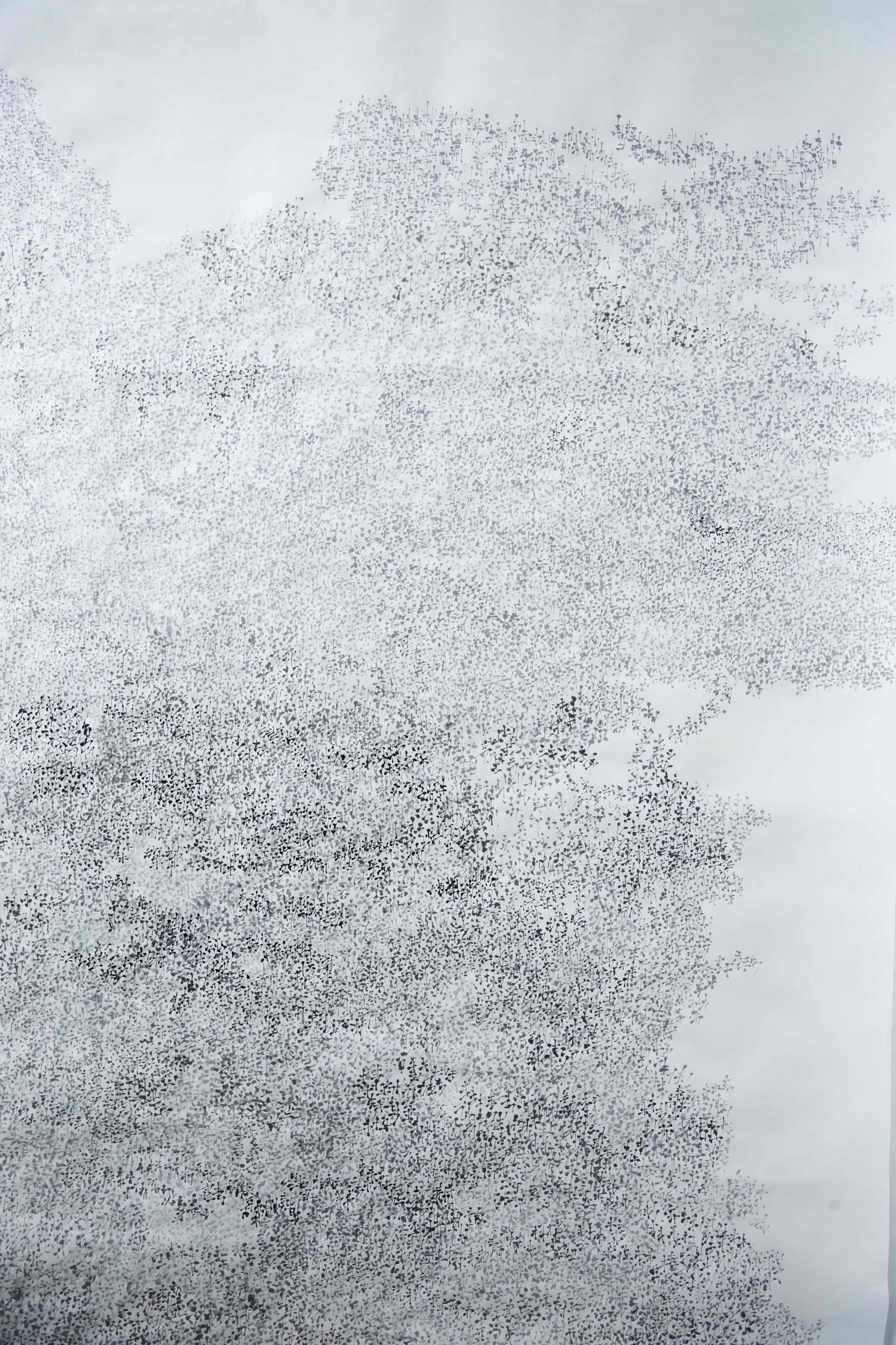

JL: Most visits were fruitful. I didn’t know how I managed it, as I didn’t have the language to speak about my work. My painting was done using simplified calligraphic strokes and dots, to make a landscape painting. I had a visitor who asked if I would do such a work for him with his name. This was when I decided to move from the idea of landscape to “non-landscape” painting. I had a friend who after studying my work, said Chinese ink monochromes should achieved five different ink tones. There were also other ideas, like should it be more banal, how do I make it saccharine sweet. And also, I became more interested in misreadings.

I do not know who would support me here in developing the work and certainly it needs more time to evolve. Different spaces might induce different outcomes. I thought I should apply for a residency in Taiwan, or just go see the mountains of China in order to further the work. I certainly have much more readings to catch up, as too much time have been spent on visualizing the work during this residency.

G: There was a session on misreadings at the last CIHA conference in Beijing, exploring the notion of creative misreadings, and how misreadings can also be productive. The question then might be how can one strategically engage with such opportunities.

JL: Yes, I agree with you, from the absurd to the common sensical. Strategically, between the definitions of what constitute the traditional, the modern, postmodern and the contemporary, one could play with the logic of a structuring, where fragmented nodal points of reference, could be linked and fissures shown. A structure with linkages and gaps, of missing grids, offering various, possible permutations, trajectories and multiple readings.

@John Low 2019 Residencies Open 25-26 January 2019 Courtesy NTU CCA Singapore