Made in Taiwan: in conversation with Yang Mao-Lin

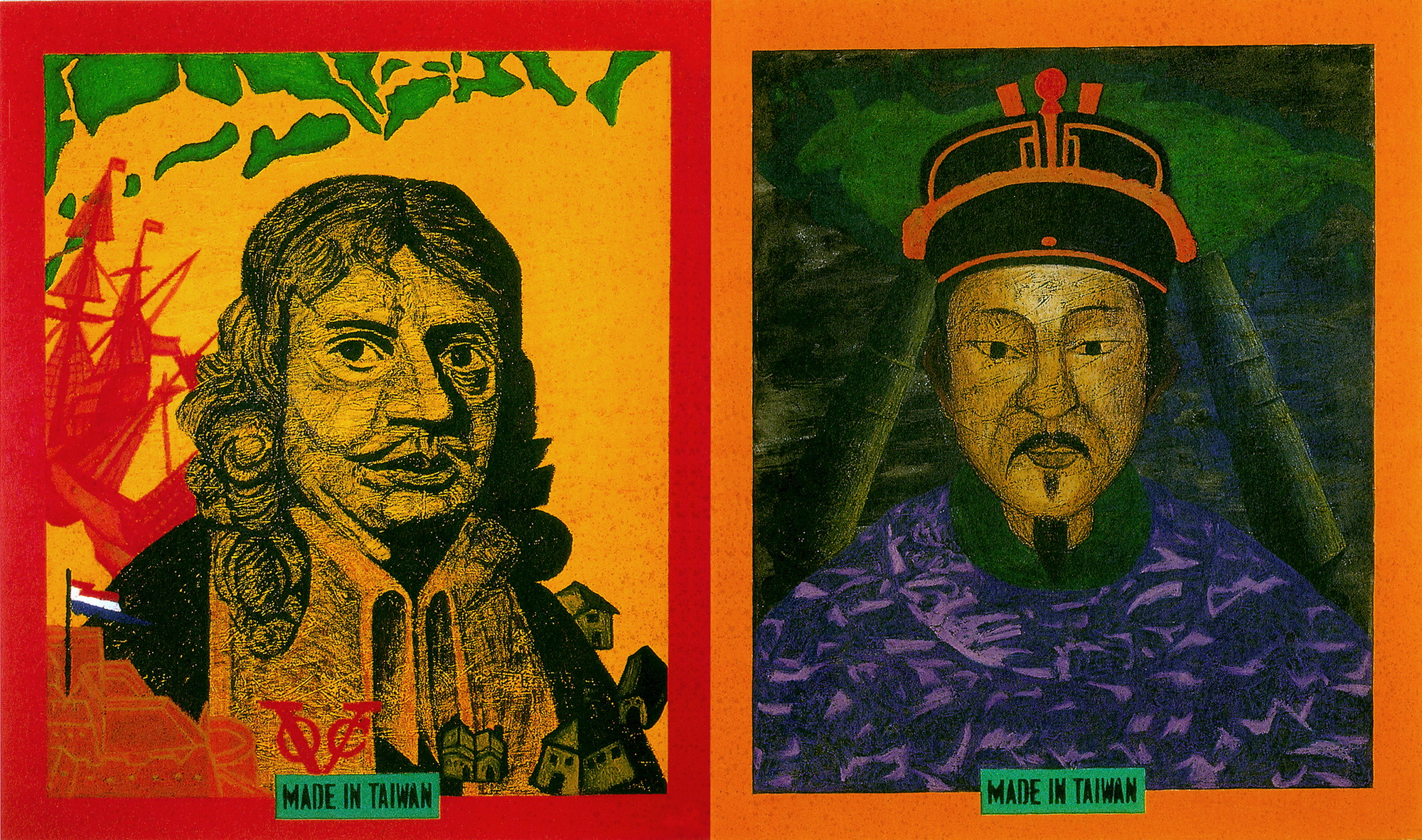

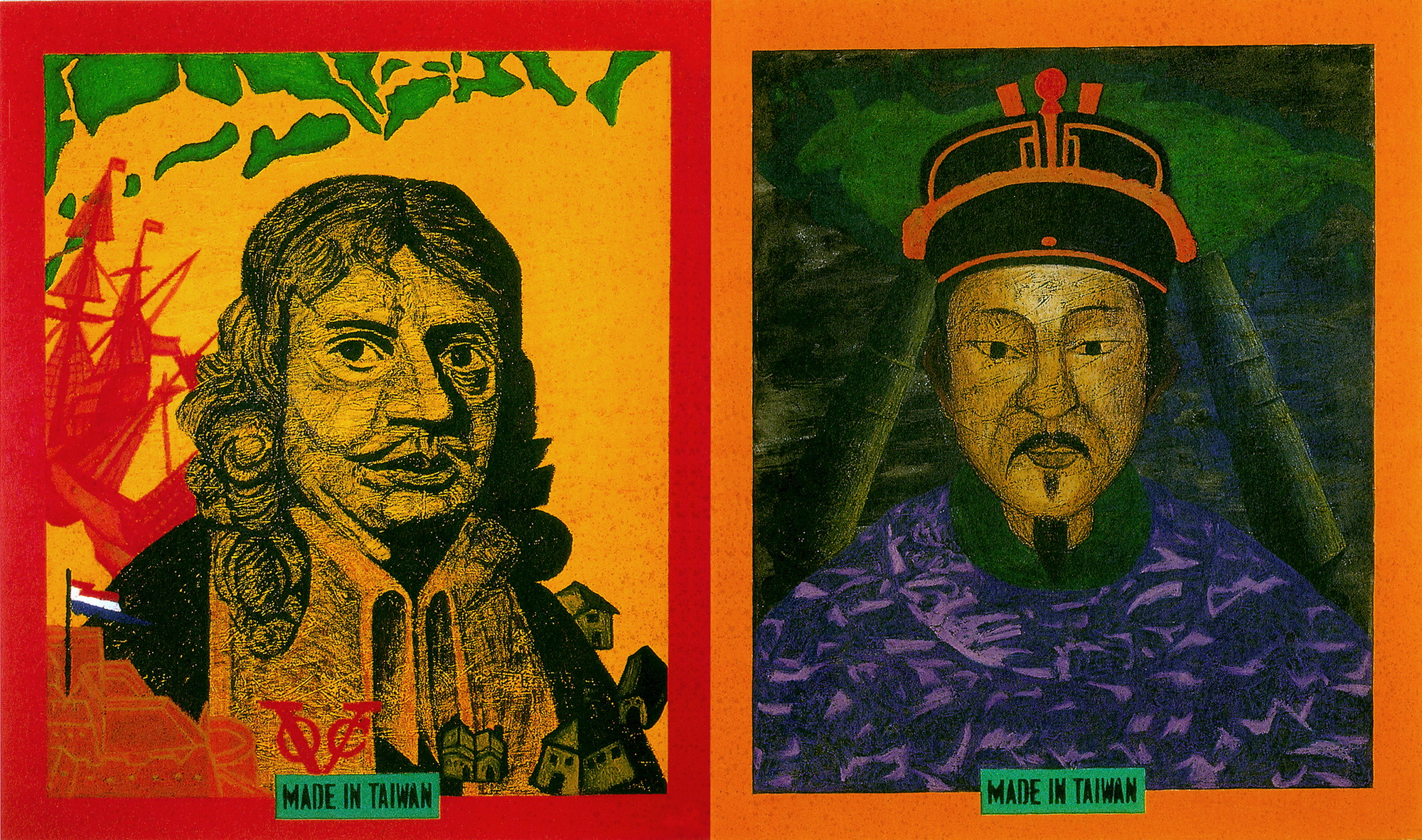

Yang Mao Lin, Zeelandia Memorandium, oil, acrylic on canvas, 112 x 194 (1993)

collected by Taipei Fine Arts Museum

Gabriel Gee in conversation with Yang Mao-Lin (08.04.2016)

With the kind assistance of Celia Lu (translation) at the Tina

Keng Gallery

Gabriel Gee: The series of paintings “Made in Taiwan”

from the 1990s attests to a strong interest in the representation of Taiwanese

history. How did you decide to engage with this history?

Yang Mao-Lin: As an artist I am interested in cultural representations, and

my work deals not so much with daily life but with historical perspectives.

Taiwan is an island that has been colonized by many different groups, and I

am particularly interested in interpreting this historical process. In my earlier

painting series from the 1980s, there was a lot of anger as I was concerned

about the historical and political issues at the time. I witnessed the development

of Taiwan from the martial law period to the end of it, followed by the shift

to democracy. My work has focused on this historical process, which led to the

series "Made in Taiwan" in the 1990s.

G.G: There are many symbolic figures represented in the paintings. How did you choose the iconographical sources?

YML: Basically, the figures in my "Zealandia Memorandum" series come

from the colonial history of Taiwan or the world, including prime ministers,

military chiefs, and missionaries of the time. As they are historical figures,

my sources were portraits that appeared in all kinds of publications. The Dutch

East India Company occupied Taiwan in the 17th century, and was later defeated

by Zheng Chenggong. This was documented in a variety of publications. With the

lifting of martial law in the 80s, greater access was granted to local publishers,

a number of which started publishing books that explored Taiwanese identity,

tracing the island's modern history all the way back to the Japanese rule and

Zheng Chenggong's rule. The images in these publications were very helpful for

my "Zealandia Memorandum" series as I am very interested in Taiwanese

identity issues. Many books published in the 1990s contained a lot of maps made

in the 17th century by Europeans, which intrigue me as well.

G.G: You include maps and figures, but there are also animals and plants in the paintings.

YML: My creative references come from Taiwanese culture and history. Two of

the series inspired by animals and plants are "Yuanshan Memorandum"

and "Lily Memorandum," which delve into the physical geography of

Taiwan inhabited then by our earliest ancestors. Different colonizers came and

went, and finally the new immigrants from the Mainland China arrived, animals

and plants flourished and decayed along the tides of history. During this process,

animals and plants of the land suffered the catastrophe together with humans.

While people were exploited and killed, flora and fauna together with the land

were also impoverished and destroyed. This should sound familiar to all the

colonized around the world. That's why I chose Taiwanese endemic and native

species, such as the Formosan clouded leopard, black bear, sika deer, and lily

— the symbol of the aborigines. However, these symbolic meanings have

been discarded after the Han Chinese took over the island. And this is why they

become motifs in my work. Later I made sculptures out of camphor driftwood that

floated from the mountains in Central and Southern Taiwan to the sea mouth in

Northern Taiwan after typhoons. Hinoki was one of my mediums as well, which

not only is easier to chisel and carve, but also has a distinctive aroma that

keeps away mosquitoes and insects. It's also a very common building material.

G.G: Your recent sculptural work also includes intersections between different historical layers. It evokes the global turn to an economy of services and the importance of information technologies with which Taiwan has been closely associated. In that respect, the 20th-century globalization of "Made in Taiwan" superposes itself to that of the 17th century, in particular through the use of emblematic figures from Japanese and Western comics.

YML: I have been engaged in the investigation of Taiwanese culture and its evolution

through my art practice. My sculptural work combines manga of the popular culture

with spiritual Buddhism to find that artistic spark. I think comics carries

a similar healing effect for children as religion does for adults, which is

why I combine the two. The characters that I adopted from Japanese manga and

American comics were part of the pop culture my children and I grew up with.

This hybrid convergence is the true face of Taiwanese culture — the result

of rich and diverse colonization.

G.G: Virtual realities are being added to our physical realities. In 'Tayouan Memorandum - preparing to delete date' however, you allude to the process of erasure with a cancellation bar that features prominently over the triptych, stating “preparing to delete.” This panel was also located strategically in the exhibition at the end of the pictorial series and just before the sculptural works.

YML: The work evokes a transition — a turning point at which Taiwan entered

democracy. Before this piece, my work mainly focused on the history from the

martial law period to its abolishment. In the process of the political transition,

there were many demonstrations. The government executed many people, political

activists in particular, and a lot of information was deleted. Not long after

this work was made, we entered a new era of democracy. In my opinion, we went

through the process of transitional justice and salvation. In the near future,

we won’t need to confront these historical and cultural issues with an

aggressive attitude. This work, therefore, turns out to be the last piece in

my historical series.

G.G: You use a range of materials in both your sculptures and paintings. What is the balance between practical concerns and possible symbolical meanings of the chosen material?

YML: The choice of material is personal. It depends on the work I’m doing,

for which I select a medium that best expresses the subject. I studied oil painting

in school, and switched to sculpture because I had to make a shrine for a project.

However, after making sculptures for a while, I started feeling restricted by

the natural shape and volume of wood, particularly with large-scale sculptures.

As a result, I shifted to bronze casting. I am considering shifting again, though

it is not certain what will come next…

G.G: The submarine appears many times in the historical series. At the end of the exhibition and in your recent body of work, sculptures of different fish seem to submerge once again.

YML: The submarine first appeared in my “Zealandia Memorandum” and

“Tayouan Memorandum” series. Looking back on history, in the 17th

century the Netherlands adapted ships of the line and submarines to fight battles,

and occupied Taiwan as its colony. Now in the 21st century, Taiwan purchases

Dutch submarines for defensive purposes. I find this rather ironic.

Back to my work, the deep-sea fishes in my sculpture series are my submarine fleets. To me, submarines are like lone wolves in the wild, like a school of Wanderers of the Abyssal Darkness. They attack independently. Every single deep-sea fish that I make is a lonely ship wandering in the ocean. There are three kinds of fish in my recent fish series: deep-sea fish, goldfish, and fighting fish. They all represent aspects of my personality. The deep-sea fish accounts for 50 percent of my personality, the goldfish 20 percent, and the fighting fish 30 percent.

Since I grew up in the countryside, I have always been interested in animals, especially fish. I find deep-sea fish very ugly yet extremely appealing, because they have developed special abilities that help them survive in dangerous environments. As an artist, I am very much part of the society, but at the same time, I like to stay a little distant from the world. In that aspect, I feel very much like a deep-sea fish.

As an artist you like to be appreciated, praised, and recognized, and this is just like the goldfish. The goldfish is mostly kept by people, so it is almost impossible for them to survive in the sea. Sometimes you have to defend yourself. That is the fighting fish part of me. As an artist, it’s very difficult to stay away from people, as you have to take part in exhibitions, show up at openings, and you are constantly being compared to other artists. In these situations, I feel very much like a fighting fish. This is why there are three types of fish that reflect my personal qualities, manifest in turn in my artistic concerns, from the political issues in the early times, to historical and popular culture, and finally to the exploration of my state of mind.

To consult Yang Mao-Lin's website click HERE