Hinterland: The eyes of the lighthouse; blood as a rover'

an exhibition in two parts at Corner College, Zurich, May-June 2018

PART 1: The eyes of the lighthouse, with, Monica Ursina Jäger, Cliona Harmey, Salvatore Vitale & Volumes library" Saturday, 5 May opening at 18h – Saturday, 26 May 2018)

PART 2: Blood as a rover, with, Jürgen Baumann, Gregory Collavini, David Jacques, Tuula Narhinen, Claudia Stöckli & Volumes library (Saturday 2 June opening at 18h - Saturday 23 June)

curated by Gabriel Gee & Anne-Laure Franchette

@Cliona Harmey 2018

Opening Hours: Wed/Thu/Fri 16:00h-19:00h & Sat 14:00h-19:00h

Discussion Part 1 Friday 11 May, 18h30: Seen Unseen, photographer Salvatore Vitale in conversation with curator Lars Willumeit

Research encounter 25-27 May: Maritime Poetics: from Coast to Hinterland limited seats, booking necessary, contact gabriel@tetigroup.org

Finissage Part 1: Saturday 26 May 18:00h artists talk with Cliona Harmey & Monica Ursina Jäger

Discussion Part 2: Tuesday 19th June 6pm th the wild", with Michael Günzburger & Lukas Bärfuss

Finissage Saturday 23d June 6pm:with a book presentation: "Changing representations of nature and cities: the 1960s and 1970s and their legacies" Gabriel Gee & Alison Vogelaar (eds.), published by Routledge, 2018.

Curatorial text:

At the turn of the 1960s-70s, a drastic shift in the representations of nature paralleled an urban revolution that signalled an intensification of global networks. The increasing interpenetration of the natural and the human realms, as well as the increasing realisation of such an interpenetration, has been a characteristic of the rise of a ‘planetary age’. On continental coasts, where the sea meets the land, ports manage the transfer of goods and the balance of offer and demand with heightened efficiency. Such maritime commerce stands as the historical engineering of our global world, accelerated by the adoption of standardised containers in the 1960s. Ships ride anonymously over the sea, the lifting sea, their bellies filled with plastic wrapped merchandise. We appear to see more afar than we used to, through digital devices and virtual fluxes, while crowds fly to distant lands that air technology has made suddenly accessible. And yet, much remains unseen in the eyes of the lighthouse, which blips to bring the sailors safely home – and their goods for the improvement of lighthouse technology in the 19th century was directly connected to mercantile interests – thereby necessarily offering dark passages and suggesting the persistence of blind spots below our promethean visions. Through the lighthouse, we can explore and question the modes of representation of our socio-natures: what is it that we see, that we can see, that we are willing to see and not able or unwilling to look at, in a contemporary age where silvery and golden profusions might well lead to blackened collapses.

@Cliona Harmey 2018

Opening Hours: Wed/Thu/Fri 16:00h-19:00h & Sat 14:00h-19:00h

Discussion Part 1 Friday 11 May, 18h30: Seen Unseen, photographer Salvatore Vitale in conversation with curator Lars Willumeit

Research encounter 25-27 May: Maritime Poetics: from Coast to Hinterland limited seats, booking necessary, contact gabriel@tetigroup.org

Finissage Part 1: Saturday 26 May 18:00h artists talk with Cliona Harmey & Monica Ursina Jäger

Discussion Part 2: Tuesday 19th June 6pm th the wild", with Michael Günzburger & Lukas Bärfuss

Finissage Saturday 23d June 6pm:with a book presentation: "Changing representations of nature and cities: the 1960s and 1970s and their legacies" Gabriel Gee & Alison Vogelaar (eds.), published by Routledge, 2018.

Curatorial text:

At the turn of the 1960s-70s, a drastic shift in the representations of nature paralleled an urban revolution that signalled an intensification of global networks. The increasing interpenetration of the natural and the human realms, as well as the increasing realisation of such an interpenetration, has been a characteristic of the rise of a ‘planetary age’. On continental coasts, where the sea meets the land, ports manage the transfer of goods and the balance of offer and demand with heightened efficiency. Such maritime commerce stands as the historical engineering of our global world, accelerated by the adoption of standardised containers in the 1960s. Ships ride anonymously over the sea, the lifting sea, their bellies filled with plastic wrapped merchandise. We appear to see more afar than we used to, through digital devices and virtual fluxes, while crowds fly to distant lands that air technology has made suddenly accessible. And yet, much remains unseen in the eyes of the lighthouse, which blips to bring the sailors safely home – and their goods for the improvement of lighthouse technology in the 19th century was directly connected to mercantile interests – thereby necessarily offering dark passages and suggesting the persistence of blind spots below our promethean visions. Through the lighthouse, we can explore and question the modes of representation of our socio-natures: what is it that we see, that we can see, that we are willing to see and not able or unwilling to look at, in a contemporary age where silvery and golden profusions might well lead to blackened collapses.

If the eyes of the lighthouse can point us towards an introspection of our perceptions and representations of 21st century planetary conditions, they might then shed light on the obscurity which surrounds the circulation of earthly materials, that fuel the light of our cities and the heat of our ever more complex technologies. It is to the blood of the land that we turn the spotlight, to gaze beneath the metal of the discreet gas and oil pipelines, to the construction of roads and canals, the baskets of railways and trucks roaming planes and mountains. We foresee the advanced state of Narcissus, peering no longer to himself in the pool of water, but inward in the woods behind him. And just like the industrial city of Tony Garnier used anthropomorphic features to organise its exemplary functioning, we look at the metabolism of the hinterland to query its desires and its health. For blood’s a rover, to use James Ellroy’s words, and beside the vitality of hybrid wild cities, loom darks shadows whose intentions or rather, projections, must be deciphered to herald the oracles of the present ... (Gabriel Gee)

Part 1 The eyes of the lighthouse:

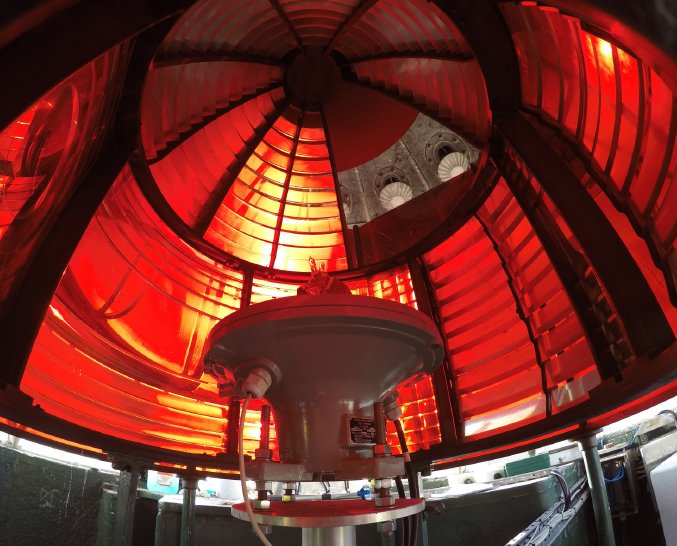

Interior of the Poolbeg Lighthouse @ Harmey 2017

Inside the Poolbeg’s lighthouse, at the very end of the Great South Wall diving off the Dublin coast into the Irish sea, we peer into a red glow. We are in a secret place, where the eyes of the common man are not meant to wander. We are inside the projector, close to the source of light that signals the mouth of the river to ships below and beyond. In its performative capacity, the lighthouse looks out into the night, in order to guide ships sailing onto the deep waters in their coastal navigation, to guide their crew to a safe haven. Lighthouses have also accompanied the extension of mercantile networks over the globe, connecting harbours, islands and continents. In a study on the development of lighthouses, Theresa Levitt retraced the modern technological improvement of lenses associated with 19th century French engineer Augustin Fresnel; she also pointed to the lighthouse’s contribution to the murky field “of money, knowledge and sea power, that bedevilled nations everywhere.” In Cliona Harmey’s work, the past and present of maritime technologies are explored through their influences on global communications and representations.

The black and white profile of an Aldis lamp switches on and off. Light, dark; visibility, invisibility. Aldis lamps were used to transmit messages in morse code at sea. In this specific sequence, the slow motion recording of the lamp’s shutters replicates Edison’s first long-distance telegraph transmission, spelling the words: ‘What hath God wrought’. Bearing in mind that telegraph connections were installed on oceans’ beds in the 19th century, thereby dramatically enhancing maritime trading operations, the work conveys the narrative of planetary connectivity, which has been at the heart of the modern industrial and cultural narrative. Similarly, the radar beacon displayed in Hinterland articulates this dialectic of vision and obscurity. Such radar reflectors are typically used at sea to make non-metallic vessels visible to radar waves. Harmey has coloured part of the beacon in black, underlining here also that the logic of localization behind the modern narrative has not been shared by all; and that the logic of ‘enlightenment’ has carried its own blind spots throughout the globe.

Monica Ursina Jäger

Interior of the Poolbeg Lighthouse @ Harmey 2017

Inside the Poolbeg’s lighthouse, at the very end of the Great South Wall diving off the Dublin coast into the Irish sea, we peer into a red glow. We are in a secret place, where the eyes of the common man are not meant to wander. We are inside the projector, close to the source of light that signals the mouth of the river to ships below and beyond. In its performative capacity, the lighthouse looks out into the night, in order to guide ships sailing onto the deep waters in their coastal navigation, to guide their crew to a safe haven. Lighthouses have also accompanied the extension of mercantile networks over the globe, connecting harbours, islands and continents. In a study on the development of lighthouses, Theresa Levitt retraced the modern technological improvement of lenses associated with 19th century French engineer Augustin Fresnel; she also pointed to the lighthouse’s contribution to the murky field “of money, knowledge and sea power, that bedevilled nations everywhere.” In Cliona Harmey’s work, the past and present of maritime technologies are explored through their influences on global communications and representations.

The black and white profile of an Aldis lamp switches on and off. Light, dark; visibility, invisibility. Aldis lamps were used to transmit messages in morse code at sea. In this specific sequence, the slow motion recording of the lamp’s shutters replicates Edison’s first long-distance telegraph transmission, spelling the words: ‘What hath God wrought’. Bearing in mind that telegraph connections were installed on oceans’ beds in the 19th century, thereby dramatically enhancing maritime trading operations, the work conveys the narrative of planetary connectivity, which has been at the heart of the modern industrial and cultural narrative. Similarly, the radar beacon displayed in Hinterland articulates this dialectic of vision and obscurity. Such radar reflectors are typically used at sea to make non-metallic vessels visible to radar waves. Harmey has coloured part of the beacon in black, underlining here also that the logic of localization behind the modern narrative has not been shared by all; and that the logic of ‘enlightenment’ has carried its own blind spots throughout the globe.

Monica Ursina Jäger

Liquid Territory @ M.U.Jäger 2018

Liquid Territory

As part of Hinterland, Monica Ursina Jäger presents a range of materials collected and produced through her investigation of Singapore’s topography, looking in particular at sand trade, cut and fill strategies and reclamation practices. Singapore has witnessed dramatic urban developments in the past fifty years, characterised by spectacular land intervention and transformation, as the city-state espoused the fortunes of our interconnected global economy. In dialogue with the work of Hans Hortig on Singapore’s ‘sand hinterland’, whose texts are incorporated into the artist’s aesthetic research, Jäger explores in Liquid Territory the fluidity of topographical mutations, architectural designs, and urban representations in the booming Malaysian trading post.

Coasts have long been privileged sites of human settlements. Coastal communities thrived on fishing, hunting and farming resources available on island and continental shores. The modern era on the one hand accentuated this connection between man and coastal sites: human hordes more than ever before migrate to the crossroads between sea and land. On the other hand, this modern passion drastically differs from traditional coastal settlements. The Singaporean coastal expansion significantly highlights this discrepancy. Sand is the fabric of new land. We see beaches and palm trees, the memories of a 19th century nascent awareness to the beauty and fascination for seashores. Yet this fascination morphed into an expansionary projection. Urban development cannot in Singapore look to a hinterland on which to build its urbanized essence and future. Consequently, behind walled gates, urban thriving takes the form of deserted horizons, to be seen on the new terrestrial platforms made out of imported sand added upon the waterfront; and subsequently, of the glistening condominiums erected upon them to host the human forces necessary to its economic drive. In effect, Singapore has inverted its hinterland, projecting it outwards onto/into the sea. The new land, however, we might reflect, erases as it creates. Old sand imported in phenomenal quantities from other nation’s shores carried archaeologic memories, which are rubbed out as the sand is transformed into the novel shorelines and cityscapes of our planetary order. These parallel histories are juxtaposed in Jäger’s work in revealing layers of the port city’s archetypal destiny.

Salvatore Vitale

Liquid Territory @ M.U.Jäger 2018

Liquid Territory

As part of Hinterland, Monica Ursina Jäger presents a range of materials collected and produced through her investigation of Singapore’s topography, looking in particular at sand trade, cut and fill strategies and reclamation practices. Singapore has witnessed dramatic urban developments in the past fifty years, characterised by spectacular land intervention and transformation, as the city-state espoused the fortunes of our interconnected global economy. In dialogue with the work of Hans Hortig on Singapore’s ‘sand hinterland’, whose texts are incorporated into the artist’s aesthetic research, Jäger explores in Liquid Territory the fluidity of topographical mutations, architectural designs, and urban representations in the booming Malaysian trading post.

Coasts have long been privileged sites of human settlements. Coastal communities thrived on fishing, hunting and farming resources available on island and continental shores. The modern era on the one hand accentuated this connection between man and coastal sites: human hordes more than ever before migrate to the crossroads between sea and land. On the other hand, this modern passion drastically differs from traditional coastal settlements. The Singaporean coastal expansion significantly highlights this discrepancy. Sand is the fabric of new land. We see beaches and palm trees, the memories of a 19th century nascent awareness to the beauty and fascination for seashores. Yet this fascination morphed into an expansionary projection. Urban development cannot in Singapore look to a hinterland on which to build its urbanized essence and future. Consequently, behind walled gates, urban thriving takes the form of deserted horizons, to be seen on the new terrestrial platforms made out of imported sand added upon the waterfront; and subsequently, of the glistening condominiums erected upon them to host the human forces necessary to its economic drive. In effect, Singapore has inverted its hinterland, projecting it outwards onto/into the sea. The new land, however, we might reflect, erases as it creates. Old sand imported in phenomenal quantities from other nation’s shores carried archaeologic memories, which are rubbed out as the sand is transformed into the novel shorelines and cityscapes of our planetary order. These parallel histories are juxtaposed in Jäger’s work in revealing layers of the port city’s archetypal destiny.

Salvatore Vitale

@Salvatore Vitale

Much further away from the shore, on a mountain slope, sheep can be seen grazing peacefully. As the night comes, they are skilfully herded together by shepherds and collie sheepdogs. Why then the ferocious sight of a canine sharp toothy mouth? Salvatore Vitale takes us into the heart of the Hinterland, in the Swiss Alps, searching for an ever elusive yet resolute presence: the wolf. Throughout Europe, wolfs which had been eradicated from plains, valleys and mountains in the nineteenth century, are making a comeback. As a tantalizing urbanization extends its ramifications throughout continental hinterlands, the need to preserve rural traditions has come in pair with a growing demand to safeguard patches of ‘nature’ and ‘wilderness’. The wolf accompanies this paradoxical phenomenon, as emotions run high over its presence amid, or beside, farming communities. The photographs were taken in the canton de Vaud and the Valais region, as part of a series taken in dialogue with a reportage by Ralph Atkins (“The return of the wolf: a Swiss identity crisis”, Financial Times, 4.08.2017;). Atkins talks to various parties, with diverging opinions on the predator. Some would want it forcibly removed, a threat to herds and man alike. Others argue for the benefit of a controlled re-introduction of the wolf, hence the toothy canine grin: to keep the wolf away from the flock. The possibility of such a cohabitation between men and wolf could signal a crucial evolution in human’s relations to nature: a move from war to peace. The re-emergence of the wolf accompanied by heated debates carries strong issues pertaining to the place of non-human species in our mixed-communities and environments. In the two spectral films taken at night amongst the sheep, Vitale unveils that which cannot be seen by the human eye. Here too, it is in the blind spot of the lighthouse that the question resides. The sound recorded at night on Alpine mountains might guide us as we strive for an answer. We might see with the painter Georgio de Chirico the first men, in a time long gone, shivering at every step, seeing omens everywhere. The key is in the question.

Part 2 Blood as a rover

@Salvatore Vitale

Much further away from the shore, on a mountain slope, sheep can be seen grazing peacefully. As the night comes, they are skilfully herded together by shepherds and collie sheepdogs. Why then the ferocious sight of a canine sharp toothy mouth? Salvatore Vitale takes us into the heart of the Hinterland, in the Swiss Alps, searching for an ever elusive yet resolute presence: the wolf. Throughout Europe, wolfs which had been eradicated from plains, valleys and mountains in the nineteenth century, are making a comeback. As a tantalizing urbanization extends its ramifications throughout continental hinterlands, the need to preserve rural traditions has come in pair with a growing demand to safeguard patches of ‘nature’ and ‘wilderness’. The wolf accompanies this paradoxical phenomenon, as emotions run high over its presence amid, or beside, farming communities. The photographs were taken in the canton de Vaud and the Valais region, as part of a series taken in dialogue with a reportage by Ralph Atkins (“The return of the wolf: a Swiss identity crisis”, Financial Times, 4.08.2017;). Atkins talks to various parties, with diverging opinions on the predator. Some would want it forcibly removed, a threat to herds and man alike. Others argue for the benefit of a controlled re-introduction of the wolf, hence the toothy canine grin: to keep the wolf away from the flock. The possibility of such a cohabitation between men and wolf could signal a crucial evolution in human’s relations to nature: a move from war to peace. The re-emergence of the wolf accompanied by heated debates carries strong issues pertaining to the place of non-human species in our mixed-communities and environments. In the two spectral films taken at night amongst the sheep, Vitale unveils that which cannot be seen by the human eye. Here too, it is in the blind spot of the lighthouse that the question resides. The sound recorded at night on Alpine mountains might guide us as we strive for an answer. We might see with the painter Georgio de Chirico the first men, in a time long gone, shivering at every step, seeing omens everywhere. The key is in the question.

Part 2 Blood as a rover

@David Jacques 2017

Visitors to the Hinterland exhibition in Zurich this month are presented with a wonderful opportunity to see three absolutely unique aquatic specimen. They were found on the shores of Finland in 2013, and are on display for the first time in Switzerland. The colourful, complex organisms of these maritime creatures can be observed at liberty in the gallery space of Corner College in Kreis 4 of the Helvetic city. Floating in large tubular glasses, their bodies partly immersed in water, these wonders of biological evolution are all part of the personal collection of the Finnish artist Tuula Närhinen, who also supplies a series of analytical drawings of these rare inhabitants of the sea she has been documenting in the maritime outskirts of Helsinki. The drawings provide curious passers-by with transversal sections and elevations of the Nordic amphibious beings. We are reminded of the great tradition of scientific observation, which can combine as in the illustrious and pioneering work of the nineteenth century German biologist Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919), meticulous attention to details with startling aesthetic effects. Haeckel these days is probably best known from the greater public for having coined the term ‘ecology’. Would he have foreseen, however, such stupendous evolutionary developments? Närhinen, who we met last week, explains that the most startling characteristics of these sea creatures, which can also be appreciated in their natural environment through a video documentary in the gallery, is that they are made of plastic! Evolution has been given a sharp twist, it appears, via our global infatuation for resins. Närhinen mused on these changing ecological patterns:

“Haeckel reflected on the manner through which everything is interconnected in the world. He made very interesting illustrations related to his research, in particular in Kunstformen der Natur, I make a connection between his work and the fantasies of the sea, between oil at the bottom of the sea and our consumption societies, whose dream material is plastic. In a way, plastic pursues the evolution in ‘the forms of nature,’ which is now out of our hands. As once plastic is within nature, it’s not in anybody’s control, and it is metamorphosing in its own in a way that we can’t observe, before coming back to human beings."

@David Jacques 2017

Visitors to the Hinterland exhibition in Zurich this month are presented with a wonderful opportunity to see three absolutely unique aquatic specimen. They were found on the shores of Finland in 2013, and are on display for the first time in Switzerland. The colourful, complex organisms of these maritime creatures can be observed at liberty in the gallery space of Corner College in Kreis 4 of the Helvetic city. Floating in large tubular glasses, their bodies partly immersed in water, these wonders of biological evolution are all part of the personal collection of the Finnish artist Tuula Närhinen, who also supplies a series of analytical drawings of these rare inhabitants of the sea she has been documenting in the maritime outskirts of Helsinki. The drawings provide curious passers-by with transversal sections and elevations of the Nordic amphibious beings. We are reminded of the great tradition of scientific observation, which can combine as in the illustrious and pioneering work of the nineteenth century German biologist Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919), meticulous attention to details with startling aesthetic effects. Haeckel these days is probably best known from the greater public for having coined the term ‘ecology’. Would he have foreseen, however, such stupendous evolutionary developments? Närhinen, who we met last week, explains that the most startling characteristics of these sea creatures, which can also be appreciated in their natural environment through a video documentary in the gallery, is that they are made of plastic! Evolution has been given a sharp twist, it appears, via our global infatuation for resins. Närhinen mused on these changing ecological patterns:

“Haeckel reflected on the manner through which everything is interconnected in the world. He made very interesting illustrations related to his research, in particular in Kunstformen der Natur, I make a connection between his work and the fantasies of the sea, between oil at the bottom of the sea and our consumption societies, whose dream material is plastic. In a way, plastic pursues the evolution in ‘the forms of nature,’ which is now out of our hands. As once plastic is within nature, it’s not in anybody’s control, and it is metamorphosing in its own in a way that we can’t observe, before coming back to human beings."

@Tuula Narhinen 2013

Närhinen’s Baltic Sea Plastic point to the spectacular impact of human materialist and technological ingenuity on the planet’s environment. Similarly, in Conduite Forcée, Gregory Collavini captures this potent metabolic extraction of energy in the canton of Valais in the Swiss Alps, photographing sites of hydraulic power supply. As the water that runs through the penstocks of these monumental infrastructures, the photographs swirl in a cloud of dissipation, oscillating between the visible and the invisible that often characterize such strategic national assets. In and amongst the mountainous landscape, we see the power plants, pipes and turbines, the dams and the glaciers above them, deserted control rooms where the measure of a supposedly transitory element is achieved, somebody’s house with a huge pipe as a modernist ornament in its garden. Matthew Gandy underlined the peculiar position of water in The fabric of space (2014), located ‘at the intersection of landscape and infrastructure’, between the private space of the modern home, and vast networks of land stratification fuelling the development of intensified urbanizations. The primary blood of our cities and indeed bodies is colourless and transparent; its control is anything but neutral.

As exemplified by Collavini’s journey into glistening penstocks, in putting aside the elevated eyes of the lighthouse, Hinterland part II: blood as a rover dives in and turns the lenses onto the ground, or rather, underground! Jürgen Baumann’s Barbara (soft penetration) has both the form of a territory seen from a great distance above the ground, from a peak or a plane, with the negative scars of engraved corridors clearly visible at such heights, and of a milling head used for piercing mountains. Barbara is for Saint Barbara, who watches over the industrious activity of miners – as well as, incidentally, of artillerymen – who plunge into the dark to extract the substance within. The disc is connected to a container filled with lubricant oil, which drips via a plastic tube to the surface of the ceramic. Lubricant oils are typically used to reduce friction, to prevent internal combustion that might be caused by the dynamic contact between surfaces. Oil, pipes, holes, extraction and erection, the piece evokes a belief in transformative chemistry, a shared motif in the spirituality of both the Christian Church and the alchemical tradition. The shape of retorts used in distillation, is not unlike that of the Pelican, symbol of abnegation and transubstantiation through the mother Pelican, who bites herself to feed her offspring; just like the alchemist must find in its inner self the elements to mutate to a higher spiritual level; or… just like our global ship extends its nets further and further into the planet to feed its excitable visions, with the risk of choking up the maternal supply. Geologists have recently declared the advent of a new geological era, the Anthropocene, succeeding to the Holocene and characterized by the drastic impact of humanity on the planet Earth. What are the new temples of this human-shaped epoch? A Black Holey Mountain, its flesh made of tar, its feet laden with black oil offerings intended for its new slimy God.

@Tuula Narhinen 2013

Närhinen’s Baltic Sea Plastic point to the spectacular impact of human materialist and technological ingenuity on the planet’s environment. Similarly, in Conduite Forcée, Gregory Collavini captures this potent metabolic extraction of energy in the canton of Valais in the Swiss Alps, photographing sites of hydraulic power supply. As the water that runs through the penstocks of these monumental infrastructures, the photographs swirl in a cloud of dissipation, oscillating between the visible and the invisible that often characterize such strategic national assets. In and amongst the mountainous landscape, we see the power plants, pipes and turbines, the dams and the glaciers above them, deserted control rooms where the measure of a supposedly transitory element is achieved, somebody’s house with a huge pipe as a modernist ornament in its garden. Matthew Gandy underlined the peculiar position of water in The fabric of space (2014), located ‘at the intersection of landscape and infrastructure’, between the private space of the modern home, and vast networks of land stratification fuelling the development of intensified urbanizations. The primary blood of our cities and indeed bodies is colourless and transparent; its control is anything but neutral.

As exemplified by Collavini’s journey into glistening penstocks, in putting aside the elevated eyes of the lighthouse, Hinterland part II: blood as a rover dives in and turns the lenses onto the ground, or rather, underground! Jürgen Baumann’s Barbara (soft penetration) has both the form of a territory seen from a great distance above the ground, from a peak or a plane, with the negative scars of engraved corridors clearly visible at such heights, and of a milling head used for piercing mountains. Barbara is for Saint Barbara, who watches over the industrious activity of miners – as well as, incidentally, of artillerymen – who plunge into the dark to extract the substance within. The disc is connected to a container filled with lubricant oil, which drips via a plastic tube to the surface of the ceramic. Lubricant oils are typically used to reduce friction, to prevent internal combustion that might be caused by the dynamic contact between surfaces. Oil, pipes, holes, extraction and erection, the piece evokes a belief in transformative chemistry, a shared motif in the spirituality of both the Christian Church and the alchemical tradition. The shape of retorts used in distillation, is not unlike that of the Pelican, symbol of abnegation and transubstantiation through the mother Pelican, who bites herself to feed her offspring; just like the alchemist must find in its inner self the elements to mutate to a higher spiritual level; or… just like our global ship extends its nets further and further into the planet to feed its excitable visions, with the risk of choking up the maternal supply. Geologists have recently declared the advent of a new geological era, the Anthropocene, succeeding to the Holocene and characterized by the drastic impact of humanity on the planet Earth. What are the new temples of this human-shaped epoch? A Black Holey Mountain, its flesh made of tar, its feet laden with black oil offerings intended for its new slimy God.

“Oil is the devil’s excrement”, so did Juan Pablo Pérez Alfonso, former ministry of energy of oil-rich Venezuela, co-founder of the OPEC (1960), warn his fellow countrymen in a 1975 speech that took stock of the country’s economic fortune. He was pointing to the perils that might come with an unprecedented flow of income, also known as the ‘Dutch decease’ in reference to the Netherland’s economic troubles following their discovery of gas reserve in the 1960s. “I call petroleum the devil’s excrement. It brings trouble. Look at this locura – waste, corruption, consumption, our public services falling apart. And debt, debt we shall have for years.” David Jacques’ eponymous animation highlights our global economy fascination and addiction with oil, a gold pitch black that carries behind scenes of prosperity and suave contentment the scent of war, devastation of the land and the fumes of hell. The narrative starts with the exiled Alfonzo bedridden in Georges Washington Hospital in 1979, where he is visited on his death bed by a diabolic creature. A black sun looms. The bowels of the earth pulse. Tentacles reach out from below to the towers above. The metaphoric hallucinatory journey begins as the time of reckoning has come, and the dance is of a deadly hue.

“Oil is the devil’s excrement”, so did Juan Pablo Pérez Alfonso, former ministry of energy of oil-rich Venezuela, co-founder of the OPEC (1960), warn his fellow countrymen in a 1975 speech that took stock of the country’s economic fortune. He was pointing to the perils that might come with an unprecedented flow of income, also known as the ‘Dutch decease’ in reference to the Netherland’s economic troubles following their discovery of gas reserve in the 1960s. “I call petroleum the devil’s excrement. It brings trouble. Look at this locura – waste, corruption, consumption, our public services falling apart. And debt, debt we shall have for years.” David Jacques’ eponymous animation highlights our global economy fascination and addiction with oil, a gold pitch black that carries behind scenes of prosperity and suave contentment the scent of war, devastation of the land and the fumes of hell. The narrative starts with the exiled Alfonzo bedridden in Georges Washington Hospital in 1979, where he is visited on his death bed by a diabolic creature. A black sun looms. The bowels of the earth pulse. Tentacles reach out from below to the towers above. The metaphoric hallucinatory journey begins as the time of reckoning has come, and the dance is of a deadly hue.

@David Jacques

@David Jacques

Blood, transparent or opaque as a rover, in need of healing, or exemption from human interference? Claudia Stöckli invites us to accompany her as she dives into the ocean’s impenetrable depths, escaping the toxic air above, catching a whale’s breath, drifting to reach the diversity of our planet’s through contact with the islands of a secret topography below; in her sound performance which is part of an ongoing project entitled Borderless poetics in fluidity, Stöckli embraces dissolution in order to lose herself, and ourselves, to better approach contemporary issues of accountability, responsibility and resilience; a possible resurrection awaits, but let’s remember blood’s a rover.

Gabriel Gee

Hinterland: the eyes of the lighthouse, blood as a rover is accompanied by a library arranged by VOLUMES, with a selection of artists books exploring different facets of the from the documentation of road construction to vernacular rural architecture, urban habitats to garden and a wood companion. A selection of audio texts selected by TETI is also available to the visitor, echoing the themes and questions brought about by the exhibit.

Special thanks to Edition Patrick Frey for its book contributions to the VOLUMES library

The exhibition is supported by the Temperatio Stiftung.

The research encounter is supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation and Franklin University, CH.