Inversed navigations: Ahmad Fuad Osman in conversation with Gabriel N. Gee

Date: 02.04.2019, Kuala Lumpur

Transcript by Daniela Baiardi

courtesy of the artist @Ahmad Fuad Osman 2016

Gabriel Gee: Your work on the navigator Enrique de Malacca comprises different mediums (Enrique de Malacca Memorial Project , 2016); it explores history and questions of historiography at the crossroad between Southeast Asian and Europeans encounters. You do so through both objects and images, including paintings

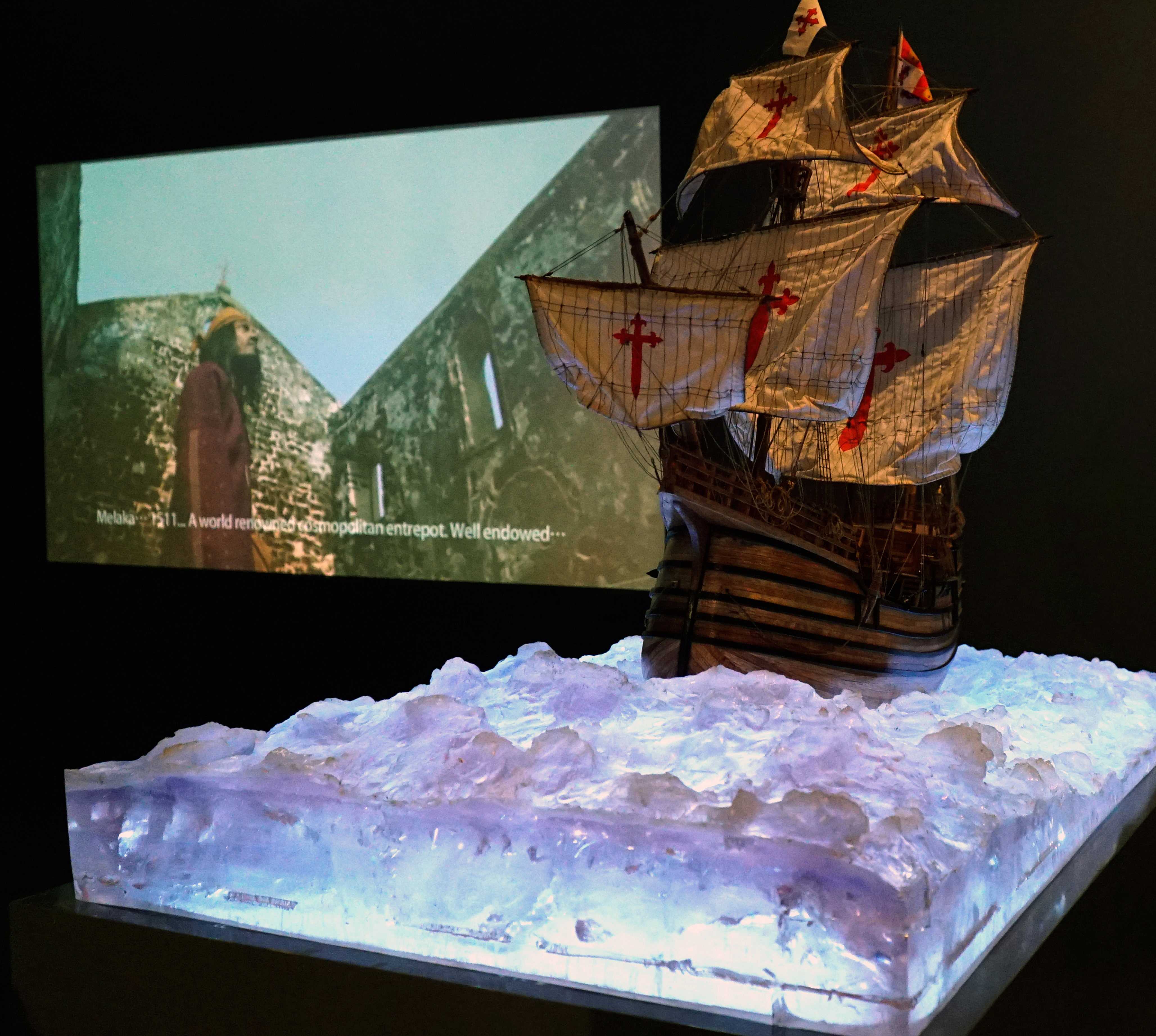

Ahmad Fuad Osman: First of all, it’s a memorial, a quite typical memorial, with paintings, sculpture, artifacts, documents, prints and objects in vitrines. The whole installation is anchored by a main video entitled ‘Imago Mundi’. The narrative of the whole story, the history of Enrique is narrated in this video. It’s easier for people to understand the whole context of the work if they watch the video from beginning to end. The whole work is a mixture of facts and fictions; it’s not totally factual. I reproduced some of the artefacts and reimagined some. Then I also included real 16th century objects within the same space. The work is also informed by my own experience. Almost every time I enter a museum I have this feeling, this suspicion regarding the objects in the museum: are they real? You look at the objects, notice how beautiful they are, how pristine, and then see that they are dated to the 11th 12th century. You start to have this doubt. It became one of the elements that I wanted to share with the public, to experience this uncertainty. Because history as you know really depends on who writes it. It’s like editing a video or film, you have so many footages, but you only choose some specific footages that really fits your narrative. Written history could be compared to this process.

courtesy of the artist @Ahmad Fuad Osman 2016

Gabriel Gee: Your work on the navigator Enrique de Malacca comprises different mediums (Enrique de Malacca Memorial Project , 2016); it explores history and questions of historiography at the crossroad between Southeast Asian and Europeans encounters. You do so through both objects and images, including paintings

Ahmad Fuad Osman: First of all, it’s a memorial, a quite typical memorial, with paintings, sculpture, artifacts, documents, prints and objects in vitrines. The whole installation is anchored by a main video entitled ‘Imago Mundi’. The narrative of the whole story, the history of Enrique is narrated in this video. It’s easier for people to understand the whole context of the work if they watch the video from beginning to end. The whole work is a mixture of facts and fictions; it’s not totally factual. I reproduced some of the artefacts and reimagined some. Then I also included real 16th century objects within the same space. The work is also informed by my own experience. Almost every time I enter a museum I have this feeling, this suspicion regarding the objects in the museum: are they real? You look at the objects, notice how beautiful they are, how pristine, and then see that they are dated to the 11th 12th century. You start to have this doubt. It became one of the elements that I wanted to share with the public, to experience this uncertainty. Because history as you know really depends on who writes it. It’s like editing a video or film, you have so many footages, but you only choose some specific footages that really fits your narrative. Written history could be compared to this process.

courtesy of the artist @Ahmad Fuad Osman 2016

Enrique de Malacca, what we know of him was that he is from this archipelago, Nusantara. But there are lots of other things about him that we’re not really sure of to this day. Even his real Malay name. What really happened to him after Magellan died and the massacre in Cebu in 1521? Where is he originally from? Indonesia, Malacca (Malaysia today), or the Philippines? These countries are still claiming him as their own, as an important figure who could possibly be the first to circumnavigate the world. Magellan is often associated with the first circumnavigation of the world, but not many people know that he was killed in Mactan, the Philippines. So, in school we were taught that the first man to circumnavigate the world is Ferdinand Magellan, he was the great navigator. And, this guy, Enrique, I like to call him an accidental navigator, maybe he was also really good, as one of the sea people. He had all these skills but not the intention of going circumnavigating the globe. Malacca had fallen to the Portuguese in 1511, he was one of the captured prisoners of war or perhaps a slave… We don’t know how they got him, whether Magellan already knew that Enrique was good at navigating and knew the way around and intentionally chose him or he was just randomly chose. We don’t know. But Magellan took him back to Portugal, became his loyal assistant, and they were together everywhere, to Morocco, then Spain. In 1519, the Armada de Molucca started its journey back from Spain in search of a new route to the Spice Islands. Since he is from the Malay Archipelago, Nusantara, once the ship reached the Philippines through the western route in 1521, he could potentially be the first man to complete the full circumnavigation of the world. But even so, for me I’m not really interested in claiming who was the first, that’s ok, but I am more interested in the missing link, the void in between those few written histories, small and personal stories about Enrique, Magellan and the voyage and also the counter claims amongst the Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia. As an artist, unlike historians, those small spaces and missing links open up so many possibilities where I can explore, re-imagine, and propose another way of looking at things . This is how the work came about.

The work was commissioned by Singapore Museum, for the Singapore Biennial in 2016. This was the first exhibition of the work.

G: This is a statue of Enrique, what is it made of?

FO: I would have liked to have it made in bronze, but in part it was a budget question, and second there was a handling problem. For a permanent museum, bronze is perfect, but this is a temporary exhibition, most probably it will be a mobile exhibition too and I don’t think it’s a good idea to have a very heavy and hard to handle piece; this one is made of fiberglass resin, with a bronze finish.

courtesy of the artist @Ahmad Fuad Osman 2016

Enrique de Malacca, what we know of him was that he is from this archipelago, Nusantara. But there are lots of other things about him that we’re not really sure of to this day. Even his real Malay name. What really happened to him after Magellan died and the massacre in Cebu in 1521? Where is he originally from? Indonesia, Malacca (Malaysia today), or the Philippines? These countries are still claiming him as their own, as an important figure who could possibly be the first to circumnavigate the world. Magellan is often associated with the first circumnavigation of the world, but not many people know that he was killed in Mactan, the Philippines. So, in school we were taught that the first man to circumnavigate the world is Ferdinand Magellan, he was the great navigator. And, this guy, Enrique, I like to call him an accidental navigator, maybe he was also really good, as one of the sea people. He had all these skills but not the intention of going circumnavigating the globe. Malacca had fallen to the Portuguese in 1511, he was one of the captured prisoners of war or perhaps a slave… We don’t know how they got him, whether Magellan already knew that Enrique was good at navigating and knew the way around and intentionally chose him or he was just randomly chose. We don’t know. But Magellan took him back to Portugal, became his loyal assistant, and they were together everywhere, to Morocco, then Spain. In 1519, the Armada de Molucca started its journey back from Spain in search of a new route to the Spice Islands. Since he is from the Malay Archipelago, Nusantara, once the ship reached the Philippines through the western route in 1521, he could potentially be the first man to complete the full circumnavigation of the world. But even so, for me I’m not really interested in claiming who was the first, that’s ok, but I am more interested in the missing link, the void in between those few written histories, small and personal stories about Enrique, Magellan and the voyage and also the counter claims amongst the Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia. As an artist, unlike historians, those small spaces and missing links open up so many possibilities where I can explore, re-imagine, and propose another way of looking at things . This is how the work came about.

The work was commissioned by Singapore Museum, for the Singapore Biennial in 2016. This was the first exhibition of the work.

G: This is a statue of Enrique, what is it made of?

FO: I would have liked to have it made in bronze, but in part it was a budget question, and second there was a handling problem. For a permanent museum, bronze is perfect, but this is a temporary exhibition, most probably it will be a mobile exhibition too and I don’t think it’s a good idea to have a very heavy and hard to handle piece; this one is made of fiberglass resin, with a bronze finish.

courtesy of the artist @Ahmad Fuad Osman 2016

G: The sound was made for the exhibition?

FO: Unfortunately not. It’s just in the main video. I thought of having a special design sound to give an immersive experience as you entered the memorial but it didn’t materialise at that time. Maybe I should work on it again for the next show.

The work was conceived as a museum, but I don’t want to call it a museum, as it sounds too big for me. Given the limited time frame given to me for the production, I could not really deliver the work in a museum scale, so I called it a memorial instead, and it became a bit more personal and intimate I guess.

G: The interstitial space suggests and exploration of alternative narratives.

FO: It is indeed an alternate narrative, an alternative history.

Gee: It also conveys a reflection on museology, and strategies through which we narrate the world. The photographer Allan Sekula in one of his last projects, the Dockers’ museum, presented artifacts he had collected related to the sea, to workers experience of the sea, sailors, people working in container ships. It stands in an in-between, revisiting Marcel Broodhaerts’ the Museum of modern art, Department of Eagles from the late 1960s, creating a sort of meta-museum, a museum about museum.

FO: I heard or must have read about Sekula’s work somewhere. It sounds very interesting but I haven’t really got a chance to get to know his project deeper which I wished I’d do in the near future. By the way, have you seen Orhan Pamuk’s ‘Museum of innocence’ in Istanbul? Of course it’s totally different in context. It is based on his book, his novel, with the same title. From what I understand, while he was writing the novel, he was already conceiving the idea of having the real museum with the characters in the book. I went there and liked the museum. It’s totally personal and fictional, but within this fictional museum, you still have the traces of real history, of Istanbul, it’s beautiful. I like it.

courtesy of the artist @Ahmad Fuad Osman 2016

G: The sound was made for the exhibition?

FO: Unfortunately not. It’s just in the main video. I thought of having a special design sound to give an immersive experience as you entered the memorial but it didn’t materialise at that time. Maybe I should work on it again for the next show.

The work was conceived as a museum, but I don’t want to call it a museum, as it sounds too big for me. Given the limited time frame given to me for the production, I could not really deliver the work in a museum scale, so I called it a memorial instead, and it became a bit more personal and intimate I guess.

G: The interstitial space suggests and exploration of alternative narratives.

FO: It is indeed an alternate narrative, an alternative history.

Gee: It also conveys a reflection on museology, and strategies through which we narrate the world. The photographer Allan Sekula in one of his last projects, the Dockers’ museum, presented artifacts he had collected related to the sea, to workers experience of the sea, sailors, people working in container ships. It stands in an in-between, revisiting Marcel Broodhaerts’ the Museum of modern art, Department of Eagles from the late 1960s, creating a sort of meta-museum, a museum about museum.

FO: I heard or must have read about Sekula’s work somewhere. It sounds very interesting but I haven’t really got a chance to get to know his project deeper which I wished I’d do in the near future. By the way, have you seen Orhan Pamuk’s ‘Museum of innocence’ in Istanbul? Of course it’s totally different in context. It is based on his book, his novel, with the same title. From what I understand, while he was writing the novel, he was already conceiving the idea of having the real museum with the characters in the book. I went there and liked the museum. It’s totally personal and fictional, but within this fictional museum, you still have the traces of real history, of Istanbul, it’s beautiful. I like it.

courtesy of the artist @Ahmad Fuad Osman 2016

G: How about the artifacts? The objects. Do you make them?

FO: Some of them yes, based on the period, the 16th century. I try to copy original materials, to get as close as possible to the originals. I also collected some objects during my research, because I went to the three countries which are claiming this guy, Malaysia, Philippines and Indonesia. During my journey I managed to find and acquire some artifacts from Cebu, Jakarta, Maluku and Melaka (Malaysia)… They represent all three countries. In some of the captions I didn’t state the provenance, and whether the objects are a reproduction or not. I want to reclaim this blurry line between fact and fiction. People don’t know if it’s real artifact or not. If we declare it, the illusion is gone. Even in a real museum, it often happens that the origins of some objects are only described as unknown. For an artist it is an opportunity to explore the more rigid territory of the historians, which makes things more interesting.

If you look at these objects here, these are reproductions, such as this sword. While these are real coins from the 16th century, and this small celadon was from the 13th century. This is a real canon ball. It’s really mixed up. This is a real shield but only about 200-300 years old, Magellan’s fleet arrived in Cebu (Philippines) 200 years earlier, but the style is still almost the same. I got this one from Cebu, Philippines, this is the type of weapons they used to fight with and which killed Magellan. For the sculpture of Enrique, how to portray him? An interpreter who never would have thought of being part of Armada de Molucca’s historical voyage? I put him down in a squatting pose. I didn’t want him to be standing like in a typical monument because in the Armada de Molucca’s context, he was just an accidental navigator. If I had put him standing proudly like a real navigator, which he is probably not, it wouldn’t do! I just had to put him down in this humble pose and more grounded. I wanted to highlight him but not as a typical heroic navigator figures such as Magellan, Columbus or Cook. He is different. All these aspects have to be taken into consideration.

courtesy of the artist @Ahmad Fuad Osman 2016

G: How about the artifacts? The objects. Do you make them?

FO: Some of them yes, based on the period, the 16th century. I try to copy original materials, to get as close as possible to the originals. I also collected some objects during my research, because I went to the three countries which are claiming this guy, Malaysia, Philippines and Indonesia. During my journey I managed to find and acquire some artifacts from Cebu, Jakarta, Maluku and Melaka (Malaysia)… They represent all three countries. In some of the captions I didn’t state the provenance, and whether the objects are a reproduction or not. I want to reclaim this blurry line between fact and fiction. People don’t know if it’s real artifact or not. If we declare it, the illusion is gone. Even in a real museum, it often happens that the origins of some objects are only described as unknown. For an artist it is an opportunity to explore the more rigid territory of the historians, which makes things more interesting.

If you look at these objects here, these are reproductions, such as this sword. While these are real coins from the 16th century, and this small celadon was from the 13th century. This is a real canon ball. It’s really mixed up. This is a real shield but only about 200-300 years old, Magellan’s fleet arrived in Cebu (Philippines) 200 years earlier, but the style is still almost the same. I got this one from Cebu, Philippines, this is the type of weapons they used to fight with and which killed Magellan. For the sculpture of Enrique, how to portray him? An interpreter who never would have thought of being part of Armada de Molucca’s historical voyage? I put him down in a squatting pose. I didn’t want him to be standing like in a typical monument because in the Armada de Molucca’s context, he was just an accidental navigator. If I had put him standing proudly like a real navigator, which he is probably not, it wouldn’t do! I just had to put him down in this humble pose and more grounded. I wanted to highlight him but not as a typical heroic navigator figures such as Magellan, Columbus or Cook. He is different. All these aspects have to be taken into consideration.

courtesy of the artist @Ahmad Fuad Osman 2016

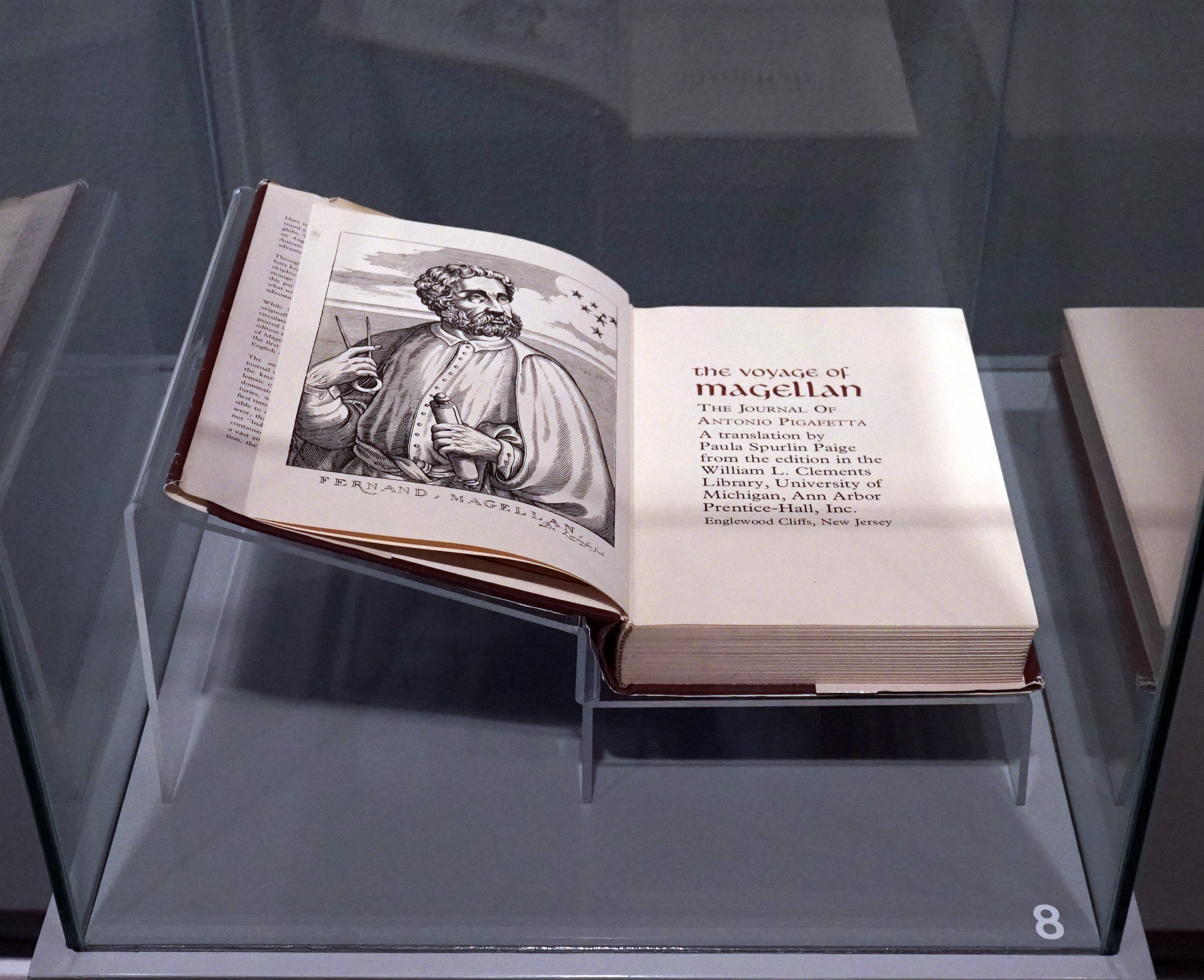

On his survival? How did he survive? He came from here, and he had never been out there before 1511, and especially not in a voyage such as the Armada de Molucca’s. It was not an easy one. If you read Antonio Pigafetta’s journal, and other accounts of the journey that they undertook, it was not an easy journey…. Started with around 260-270 men on board, at the end only 18 survived. He was one of the survivors, which would make them 19. They had to confront extreme hot and cold weather conditions, typhoons, storms, facing a mutiny, shortage of food supplies, faced malnutrition, scurvy, and then also the politics and constant tension between Portuguese and Spanish, who didn’t trust each other, causing troubles along the way. He also had to face jealousy, suspicion and racial politics of Europeans upon the outsiders. He survived all those things. I have to think of how he actually made it. It could not possibly be only physical and mental strength. It had to be more than that. This is one of the things that I personally instilled in him for the project, the strength of spirituality. Because in 16th century Nusantara, Islam was already rooted and strong, particularly Sufism, which stresses the spiritual side of human existence rather than the physical and mental alone. For him to survive the journey, if you remember the words in the main video, if you can surrender and accept whatever that comes your way, destined for you, you will easily survive. Psychologically, if you try very hard to fight against this and that, it will be stressful, and a lot of this come with that. If you have this philosophy of life, this understanding that came from religious teachings, the faith, then you become more relaxed, accepting everything that comes your way. We don’t know what really happened to him. In Sufism, the most important thing for someone is the heart. For me, I believe that if he came from here he must have been a Muslim because Islam was already around in the Malay Archipelago since before the 9th century. When he was taken on board a Portuguese ship after the fall of Malacca, they baptized him as a Christian. Some people said that he was a converted, in Malay we say a murtad, he changed his religion, from Muslim to Christian. Personally, I think he had no choice as a prisoner of war, or a slave. He was captured. If they baptized him, he must have accepted it. Most probably because of his survival. But we don’t really know for sure. In Sufi’s teaching it is not the eye but the heart that ‘perceives’. It’s not important what is outside rather than the inside, it is what is in the heart that matters. Outside you can be concealed or be whoever you want to be but deep inside, you just hold on to your faith.

There is also an aspect of shamanism that I used in the ‘Imago Mundi’ video; a mantra, a charm, a magic spell. White magic. Small number of Malays are still using it today but it was quite common in the old days. Some people don’t believe in it anymore today, but some still do. In the film, I used this to justify how and why Enrique was so close, fully protected and special to Magellan. In his last will and testament, Magellan even put Enrique’s name, which says that if he should die in the journey, Enrique would automatically be freed. He started a slave and became an interpreter, a position that was quite high, even higher than that of Pigafetta, who wrote the journal. Pigafetta was paid 800 maravedis while Enrique got 1500 per month for three years, which was quite high. So, again, how could he become so close and so special to Magellan? For me, again, as an artist who is working with historical facts and evidence as my main materials here, I saw an opportunity to re-imagine and re-interpret the situation, so I made Enrique use a certain mantra. In the video, I have him at one point using the charm; Malay magic, for self protection, and for people to respect and love him.

I also have 4 iPads in the exhibition, with 30 short video interviews, from scholars in the fields of anthropology, archeology, history, coming from Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines, talking about Enrique de Malacca and the 16th century maritime history of the Age of Discovery, Spice Islands and Southeast Asia. From these video interviews, you can’t pin him down, there is no linear narrative. You as an audience at the end of the day have to decide where you want to put him. For me I don’t want him to be fixed within a single point of view. It’ll become a full stop to the whole narratives. It’s important to kind of loosen up the narrative a bit, to put him within this multiple entry point, so that people would still be able to approach the work from different angles or perspectives. I wanted him to be free, also for the viewer.

The other video I did was another fictional video, where I was supposed to meet a descendent of Enrique, here in Malaysia. Because one theory which developed especially in Malaysia, is that after the skirmish on Mactan island, he survived, while Magellan was killed, then there was another massacre in Cebu, which he also survived. Some people believe that if he came from Malacca, he must be Malay, though there was no Malaysia at that time. But since Malacca was still under the Portuguese, he came back here but ended up in one of the states called Negeri Sembilan, because there were many Indonesian communities and settlements. So, he ended up with these people, who didn’t call him Enrique, but called him Dato Laut Dalam instead. A local historian even found a grave of Dato Laut Dalam in Negeri Sembilan. Dato (or its variant Datuk or Datu) is a respected high ranking Malay title commonly used in Brunei and Malaysia, as well as a traditional title by Minangkabau people in Indonesia, and Laut Dalam would literally be translated as ‘deep sea’, which perfectly reflects Enrique’s 10 years experience with Magellan.

One day I went to meet this decendent of Dato Laut Dalam, who was supposed to keep all these artifacts. So all these artifacts which I’m exhibiting now are supposed to come from this descendent. With the objects I brought back from Cebu, and Maluku, I thought and felt that the narrative is not strong enough. I need to strengthen it. And if I have a descendent of Dato Laut Dalam, they are not necessarily the artifacts of Enrique. Because in the historical accounts, the real written history, you have some accounts on Enrique, but not Dato Laut Dalam, so these objects or artifacts are supposed to have been inherited from Dato Laut Dalam. This twist or additional subplot is important to complicate the linear narrative. Even if the artifacts did really come from Dato Laut Dalam, it’s not from a descendent of Enrique, unless he is really Enrique, which is hard to prove.

G: The documentary videos help bring the public to consider the contemporary aspects of the story, the manner through which we write history, specifically here in Malaysia?

FO: I discovered the story from a novel, entitled Panglima Awang, who is actually Enrique de Malacca, written by Harun Aminurrashid in 1957 and published in 1958. Harun doesn’t want to call him Enrique because he wanted to localize the character. Historically, we just know him as Enrique. You read the book, and then meet some Malaysian historian, who when they talk about the history of this character they actually are referring to the book! I know, because I read the book. Their knowledge of Enrique came from the book, which is already an alternate history. I thought it’s absurd that historians, respected historians, are talking about history and trying to give some historical perspective to this character… and it turns out that their sources are from this book ! So, it became a second layer of alternative history. Just imagine, if some people who are interested in Enrique’s history but know nothing at all about Harun’s book, end up talking to these historians, they would take the story as history! Fiction became facts.

courtesy of the artist @Ahmad Fuad Osman 2016

On his survival? How did he survive? He came from here, and he had never been out there before 1511, and especially not in a voyage such as the Armada de Molucca’s. It was not an easy one. If you read Antonio Pigafetta’s journal, and other accounts of the journey that they undertook, it was not an easy journey…. Started with around 260-270 men on board, at the end only 18 survived. He was one of the survivors, which would make them 19. They had to confront extreme hot and cold weather conditions, typhoons, storms, facing a mutiny, shortage of food supplies, faced malnutrition, scurvy, and then also the politics and constant tension between Portuguese and Spanish, who didn’t trust each other, causing troubles along the way. He also had to face jealousy, suspicion and racial politics of Europeans upon the outsiders. He survived all those things. I have to think of how he actually made it. It could not possibly be only physical and mental strength. It had to be more than that. This is one of the things that I personally instilled in him for the project, the strength of spirituality. Because in 16th century Nusantara, Islam was already rooted and strong, particularly Sufism, which stresses the spiritual side of human existence rather than the physical and mental alone. For him to survive the journey, if you remember the words in the main video, if you can surrender and accept whatever that comes your way, destined for you, you will easily survive. Psychologically, if you try very hard to fight against this and that, it will be stressful, and a lot of this come with that. If you have this philosophy of life, this understanding that came from religious teachings, the faith, then you become more relaxed, accepting everything that comes your way. We don’t know what really happened to him. In Sufism, the most important thing for someone is the heart. For me, I believe that if he came from here he must have been a Muslim because Islam was already around in the Malay Archipelago since before the 9th century. When he was taken on board a Portuguese ship after the fall of Malacca, they baptized him as a Christian. Some people said that he was a converted, in Malay we say a murtad, he changed his religion, from Muslim to Christian. Personally, I think he had no choice as a prisoner of war, or a slave. He was captured. If they baptized him, he must have accepted it. Most probably because of his survival. But we don’t really know for sure. In Sufi’s teaching it is not the eye but the heart that ‘perceives’. It’s not important what is outside rather than the inside, it is what is in the heart that matters. Outside you can be concealed or be whoever you want to be but deep inside, you just hold on to your faith.

There is also an aspect of shamanism that I used in the ‘Imago Mundi’ video; a mantra, a charm, a magic spell. White magic. Small number of Malays are still using it today but it was quite common in the old days. Some people don’t believe in it anymore today, but some still do. In the film, I used this to justify how and why Enrique was so close, fully protected and special to Magellan. In his last will and testament, Magellan even put Enrique’s name, which says that if he should die in the journey, Enrique would automatically be freed. He started a slave and became an interpreter, a position that was quite high, even higher than that of Pigafetta, who wrote the journal. Pigafetta was paid 800 maravedis while Enrique got 1500 per month for three years, which was quite high. So, again, how could he become so close and so special to Magellan? For me, again, as an artist who is working with historical facts and evidence as my main materials here, I saw an opportunity to re-imagine and re-interpret the situation, so I made Enrique use a certain mantra. In the video, I have him at one point using the charm; Malay magic, for self protection, and for people to respect and love him.

I also have 4 iPads in the exhibition, with 30 short video interviews, from scholars in the fields of anthropology, archeology, history, coming from Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines, talking about Enrique de Malacca and the 16th century maritime history of the Age of Discovery, Spice Islands and Southeast Asia. From these video interviews, you can’t pin him down, there is no linear narrative. You as an audience at the end of the day have to decide where you want to put him. For me I don’t want him to be fixed within a single point of view. It’ll become a full stop to the whole narratives. It’s important to kind of loosen up the narrative a bit, to put him within this multiple entry point, so that people would still be able to approach the work from different angles or perspectives. I wanted him to be free, also for the viewer.

The other video I did was another fictional video, where I was supposed to meet a descendent of Enrique, here in Malaysia. Because one theory which developed especially in Malaysia, is that after the skirmish on Mactan island, he survived, while Magellan was killed, then there was another massacre in Cebu, which he also survived. Some people believe that if he came from Malacca, he must be Malay, though there was no Malaysia at that time. But since Malacca was still under the Portuguese, he came back here but ended up in one of the states called Negeri Sembilan, because there were many Indonesian communities and settlements. So, he ended up with these people, who didn’t call him Enrique, but called him Dato Laut Dalam instead. A local historian even found a grave of Dato Laut Dalam in Negeri Sembilan. Dato (or its variant Datuk or Datu) is a respected high ranking Malay title commonly used in Brunei and Malaysia, as well as a traditional title by Minangkabau people in Indonesia, and Laut Dalam would literally be translated as ‘deep sea’, which perfectly reflects Enrique’s 10 years experience with Magellan.

One day I went to meet this decendent of Dato Laut Dalam, who was supposed to keep all these artifacts. So all these artifacts which I’m exhibiting now are supposed to come from this descendent. With the objects I brought back from Cebu, and Maluku, I thought and felt that the narrative is not strong enough. I need to strengthen it. And if I have a descendent of Dato Laut Dalam, they are not necessarily the artifacts of Enrique. Because in the historical accounts, the real written history, you have some accounts on Enrique, but not Dato Laut Dalam, so these objects or artifacts are supposed to have been inherited from Dato Laut Dalam. This twist or additional subplot is important to complicate the linear narrative. Even if the artifacts did really come from Dato Laut Dalam, it’s not from a descendent of Enrique, unless he is really Enrique, which is hard to prove.

G: The documentary videos help bring the public to consider the contemporary aspects of the story, the manner through which we write history, specifically here in Malaysia?

FO: I discovered the story from a novel, entitled Panglima Awang, who is actually Enrique de Malacca, written by Harun Aminurrashid in 1957 and published in 1958. Harun doesn’t want to call him Enrique because he wanted to localize the character. Historically, we just know him as Enrique. You read the book, and then meet some Malaysian historian, who when they talk about the history of this character they actually are referring to the book! I know, because I read the book. Their knowledge of Enrique came from the book, which is already an alternate history. I thought it’s absurd that historians, respected historians, are talking about history and trying to give some historical perspective to this character… and it turns out that their sources are from this book ! So, it became a second layer of alternative history. Just imagine, if some people who are interested in Enrique’s history but know nothing at all about Harun’s book, end up talking to these historians, they would take the story as history! Fiction became facts.

courtesy of the artist @Ahmad Fuad Osman 2016

G: At the end of the encounter with this descendent you leave the house to search for objects?

FO: Not the objects but the place where those objects came into the hands of his great grandfather. Because it’s quite common, some treasured objects are found buried under the ground. Some consider it superstition, but it has still somehow survived and is very much alive to this day. A Malay ‘magical realism’. This is also an interesting component of Malay culture and tradition that I’d like to highlight in the project. Together with the mantra that I mentioned earlier. This old wisdom, sometimes came in the form of dreams; an old man with long white beard, wearing white robe, would communicate with you in your dreams, telling you about a certain thing at a place you’re familiar with, and then, tomorrow morning you went there, searched for the spot that the old man told you about, you dug around the area and you found something. This is quite common in Southeast Asia, or in the Malay Archipelago. So, within this work I wanted to bring out all these components. Some of the objects displayed in the Memorial Project, came to his great grandfather through his dream.

G: Facts merge with fiction, yet in a mode that does not play into the hand of political manipulation but rather favour critical awareness. You have explored this political dimension in the past in your work, in Close up?

FO: That one is political, controversial, although today is different, this was done during the last government. It became a book project. Do you know about this big controversial corruption scandal in Malaysia? 1MDB as it is known. It’s quite complex. Billions of dollars syphoned from sovereign wealth fund.

Our ex-Prime minister, Mr. Najib Razak was partly involved by approving and signing off some official letters. He is on trial now for the biggest corruption and abuse of political power in Malaysia history. In our traditional shadow puppet theatre, the one who holds the puppets is called Tok Dalang. In this case we had one key person holding the strings, a business man from Penang called Low Taek Jho or better known as Jho Low who is now a fugitive, still at large. He was the one who plotted and managed all the interbank money transfers, national and internationally. For some years at that time we all knew that billions of dollars were being syphoned by him, but we didn’t have the power to do anything about it, as the government, and the Prime Minister himself held the power firmly; we couldn’t really criticize it openly at that time while this Tok Dalang were spending the money partying with celebrities like Leonardo di Caprio, Paris Hilton, Alicia Keys, Kanye West and a few others in high end night clubs in New York and London. I felt an urgency and an urge to address the issue, to document it even if it’s just for my family and close friends. Again, if in the last election (2018) the previous government had won the elections and were still in power today, all these issues would automatically be closed or erased by now. It would be a different history altogether. As an artist, I need to do something about it, to document and provide an alternative history but how to talk about it indirectly? I was lucky because apart from just partying with celebrities, the puppet master also collects arts. This is the entry point for me to talk about the issue. Interestingly, also through arts. I started to do a research on his collection. In 2013 he made headlines by outbidding some world renown art collectors at a Christie’s auction for a Jean Michel Basquiat’s painting. That’s how we came to know about him, for suddenly the world was talking about a Malaysian collector, who owns a $48.8 million dollars Basquiat’s Dustheads. Who is this guy? Where is he from? What does he do for a living? Because of his Basquiat’s painting, I started to do a bit more research on him and his art collection. Apparently he owns a lot more. Picasso, Richter, Monet and Rothko’s among others. I compiled this research. Initially I thought of an installation piece on the findings, but there was no substantial exhibition around and you couldn’t talk openly about it at that time. So I just compiled it, toying around with some possibilities and at last, decided on publishing it as a limited edition artist’s book. It contains a detailed background of each of the paintings he collected, who were the artists and why they painted the work, the provenance and the most important thing, the price of every single artwork, which was of course, paid with the syphoned money, the Malaysian taxpayer’s money.

G. It’s another aspect of hidden stories, with a detective side to it.

FO: The attorney general of that time cleared the prime minister. And who can argue? Justice and judiciary system was all in his hand. After we changed the government in the last election, things changed. So that’s another aspect of my work. I don’t like politics, but we can’t really get away from it, it’s part of our lives. We are part of it, we are in the system, whether you like it or not. You wake up in the morning, talking with friends, sharing things about all this headlines you or they saw and read because it’s everywhere. You can’t get away. And it comes out again in your work at the end of the day. It has been like that for most of my work all these years. With those newspaper headlines, you see the power of media, their capacity to manipulate; with the right image and captions, they can change the perception of people altogether.

G: You also like to mix different association and symbols.

FO: It depends on the concept and context of the work. My practice is quite fluid on the dynamics of forms, styles, subject matters, or even the use of materials. It really depends on the ideas I wanted to explore and talk about at certain time. It’s important for me to be free on those parts. If I need to produce a book, I produce a book, If I need an installation to talk about a single character, I produce an installation. For instance, my EDM Memorial Project. Enrique de Malacca is such an important figure in the epic and historic Armada de Molucca’s voyage in our collective history and imaginaries. How should he be presented? I cannot present him through just one object, a sculpture or a painting. I need to place him within a bigger context. A lot of considerations, negotiations, and decision making are involved in the process. It really depends on that. The idea will dictate my choices and used of materials and its presentation. I just can’t understand the artist who talks about only one thing for his whole life, whether it’s a subject matter or style, focusing on just one particular thing. I can’t see the logic of this today. Maybe in the 1960’s, in the modernist period, for the artist to find a specific form and just stick to it was okay. But today with all these hi-tech, advanced technologies, AI, smartphones with multiple social media sharing platforms as we are constantly bombarded by all kinds of texts and images day in day out. And you choose to talk only about just one thing, one form or style, or technique or medium? I cannot understand it. At least for now.

for more information on the Enrique de Malacca Memorial, see the project online resources

courtesy of the artist @Ahmad Fuad Osman 2016

G: At the end of the encounter with this descendent you leave the house to search for objects?

FO: Not the objects but the place where those objects came into the hands of his great grandfather. Because it’s quite common, some treasured objects are found buried under the ground. Some consider it superstition, but it has still somehow survived and is very much alive to this day. A Malay ‘magical realism’. This is also an interesting component of Malay culture and tradition that I’d like to highlight in the project. Together with the mantra that I mentioned earlier. This old wisdom, sometimes came in the form of dreams; an old man with long white beard, wearing white robe, would communicate with you in your dreams, telling you about a certain thing at a place you’re familiar with, and then, tomorrow morning you went there, searched for the spot that the old man told you about, you dug around the area and you found something. This is quite common in Southeast Asia, or in the Malay Archipelago. So, within this work I wanted to bring out all these components. Some of the objects displayed in the Memorial Project, came to his great grandfather through his dream.

G: Facts merge with fiction, yet in a mode that does not play into the hand of political manipulation but rather favour critical awareness. You have explored this political dimension in the past in your work, in Close up?

FO: That one is political, controversial, although today is different, this was done during the last government. It became a book project. Do you know about this big controversial corruption scandal in Malaysia? 1MDB as it is known. It’s quite complex. Billions of dollars syphoned from sovereign wealth fund.

Our ex-Prime minister, Mr. Najib Razak was partly involved by approving and signing off some official letters. He is on trial now for the biggest corruption and abuse of political power in Malaysia history. In our traditional shadow puppet theatre, the one who holds the puppets is called Tok Dalang. In this case we had one key person holding the strings, a business man from Penang called Low Taek Jho or better known as Jho Low who is now a fugitive, still at large. He was the one who plotted and managed all the interbank money transfers, national and internationally. For some years at that time we all knew that billions of dollars were being syphoned by him, but we didn’t have the power to do anything about it, as the government, and the Prime Minister himself held the power firmly; we couldn’t really criticize it openly at that time while this Tok Dalang were spending the money partying with celebrities like Leonardo di Caprio, Paris Hilton, Alicia Keys, Kanye West and a few others in high end night clubs in New York and London. I felt an urgency and an urge to address the issue, to document it even if it’s just for my family and close friends. Again, if in the last election (2018) the previous government had won the elections and were still in power today, all these issues would automatically be closed or erased by now. It would be a different history altogether. As an artist, I need to do something about it, to document and provide an alternative history but how to talk about it indirectly? I was lucky because apart from just partying with celebrities, the puppet master also collects arts. This is the entry point for me to talk about the issue. Interestingly, also through arts. I started to do a research on his collection. In 2013 he made headlines by outbidding some world renown art collectors at a Christie’s auction for a Jean Michel Basquiat’s painting. That’s how we came to know about him, for suddenly the world was talking about a Malaysian collector, who owns a $48.8 million dollars Basquiat’s Dustheads. Who is this guy? Where is he from? What does he do for a living? Because of his Basquiat’s painting, I started to do a bit more research on him and his art collection. Apparently he owns a lot more. Picasso, Richter, Monet and Rothko’s among others. I compiled this research. Initially I thought of an installation piece on the findings, but there was no substantial exhibition around and you couldn’t talk openly about it at that time. So I just compiled it, toying around with some possibilities and at last, decided on publishing it as a limited edition artist’s book. It contains a detailed background of each of the paintings he collected, who were the artists and why they painted the work, the provenance and the most important thing, the price of every single artwork, which was of course, paid with the syphoned money, the Malaysian taxpayer’s money.

G. It’s another aspect of hidden stories, with a detective side to it.

FO: The attorney general of that time cleared the prime minister. And who can argue? Justice and judiciary system was all in his hand. After we changed the government in the last election, things changed. So that’s another aspect of my work. I don’t like politics, but we can’t really get away from it, it’s part of our lives. We are part of it, we are in the system, whether you like it or not. You wake up in the morning, talking with friends, sharing things about all this headlines you or they saw and read because it’s everywhere. You can’t get away. And it comes out again in your work at the end of the day. It has been like that for most of my work all these years. With those newspaper headlines, you see the power of media, their capacity to manipulate; with the right image and captions, they can change the perception of people altogether.

G: You also like to mix different association and symbols.

FO: It depends on the concept and context of the work. My practice is quite fluid on the dynamics of forms, styles, subject matters, or even the use of materials. It really depends on the ideas I wanted to explore and talk about at certain time. It’s important for me to be free on those parts. If I need to produce a book, I produce a book, If I need an installation to talk about a single character, I produce an installation. For instance, my EDM Memorial Project. Enrique de Malacca is such an important figure in the epic and historic Armada de Molucca’s voyage in our collective history and imaginaries. How should he be presented? I cannot present him through just one object, a sculpture or a painting. I need to place him within a bigger context. A lot of considerations, negotiations, and decision making are involved in the process. It really depends on that. The idea will dictate my choices and used of materials and its presentation. I just can’t understand the artist who talks about only one thing for his whole life, whether it’s a subject matter or style, focusing on just one particular thing. I can’t see the logic of this today. Maybe in the 1960’s, in the modernist period, for the artist to find a specific form and just stick to it was okay. But today with all these hi-tech, advanced technologies, AI, smartphones with multiple social media sharing platforms as we are constantly bombarded by all kinds of texts and images day in day out. And you choose to talk only about just one thing, one form or style, or technique or medium? I cannot understand it. At least for now.

for more information on the Enrique de Malacca Memorial, see the project online resources